When I met Bruce McLAREN

On the anniversary of Bruce McLaren’s death, Simon Taylor, former editor of Autosport, shares his memories of our team’s founder.

Last Sunday, as that dramatic Monaco Grand Prix unreeled on millions of television screens around the world, those of us with long enough memories were thinking back 50 years to Monaco 1966, and the first time a McLaren car was wheeled onto a Formula 1 starting grid. So many McLaren things have happened in the ensuing half-century, so many articles written, photographs taken, books published, films made – and races and championships won – that it is much easier to refocus that widescreen rush of facts down to a personal close-up of Bruce McLaren. In my own small way, I am fortunate enough to be able to do that.

Half a century ago, while the tiny McLaren team was getting the M2B ready for its first race, I was sitting my finals at Cambridge. I had vague, unformed dreams of finding a way of making a living from going to motor races, rather than putting on a suit every morning and carrying a cheese and tomato sandwich and a rolled umbrella onto an Underground train. I didn’t think they would ever be more than dreams. But four weeks later – due to an extraordinary conjunction of coincidence and good fortune – I found myself being paid £8 a week to be the most junior of the three-man editorial staff on Autosport, whose masthead proudly announced that it was Britain’s Motor Sporting Weekly.

I was given a standard 850cc Mini and told to cover club races – typically Castle Combe (Wiltshire) on Saturday, Cadwell Park (Lincolnshire) on Sunday, and the next weekend Rufforth (Yorkshire) on Saturday, Lydden Hill (Kent) on Sunday. On Monday and Tuesday we put the magazine to press, working on our portable typewriters at the printers – no computers, no email, not even fax then. On Thursday and Friday we worked in a tiny office over a pornographic bookshop in Paddington, writing features. Wednesday was for crashing out, and the launderette. I got very little sleep, and my Mini clocked up a prodigious mileage, always flat-out at its maximum speed of 73.4mph. I loved every minute, and it was certainly better than working. But it wasn’t until some months later that I was allowed to venture abroad to the occasional Formula 2 race. And in May 1967 I found myself in Belgium, at Zolder, covering the Grand Prix du Limbourg.

RELATED ARTICLE SMALL

The wonderful thing about Formula 2 then was that it was contested not only by young hopefuls, like Chris Irwin, Alan Rollinson, my flat-mate Chris Lambert and Max Mosley (whatever happened to him?) but also by most of the established Grand Prix drivers: Jimmy Clark, Jochen Rindt, Jackie Stewart, Jack Brabham and the rest.

And by Bruce McLaren. Somehow, along with building and running his own team, and now fielding his M5A-BRM in Formula 1 and his M6A-Chevrolets in CanAm – not to mention endurance racing in the mighty works Ford Mk II – that season Bruce was also managing to contest Formula 2 with his M4A-Cosworth.

I was already friendly with most of the hopefuls but, still very wet behind the ears, I was diffident about approaching the stars. During Friday practice I watched Bruce McLaren wandering around the paddock with that slightly limping walk, wrapped up in thought as he looked quizzically at different details of his rivals’ cars. Choosing my moment I went up to him and introduced myself, in order to ask him a trivial reporter’s question.

At once the quizzical look was replaced by a dazzling, friendly smile. He listened to my question, took it seriously, thought for a moment and then gave me a detailed and constructive answer.

"Even a scruffy near-adolescent journalist was treated as an equal, and with courtesy."

It was my first conversation with a man I came to admire deeply. I can’t claim that I ever got to know him well, but from then on I always found him good-humoured and entirely unpatronising. Even a scruffy near-adolescent journalist was treated as an equal, and with courtesy. In a way that is difficult to imagine from the viewpoint of today’s highly charged Formula 1 media circus, there was no self-importance. He was always approachable, he never seemed to be under pressure, and his friendliness and relaxed manner seemed never to waver.

Three years later, June 2nd 1970 was a Tuesday. Slightly drier behind the ears, I had been promoted to Editor of Autosport, probably because I was even keener than the rest and prepared to clock up more miles in my Mini. In those letterpress days the tiny editorial team would usually spend around 32 hours – all day Monday, Monday night, and Tuesday until late afternoon – in a noisome portakabin beside the roaring printing machines in a warehouse in north London. We kept going on fish ’n’ chips from the unhealthy chippy around the corner, and in the small hours I would sneak out into the car park. The Mini, driven into the ground, had been replaced by a second-hand Cortina, and I would snatch forty winks on the back seat.

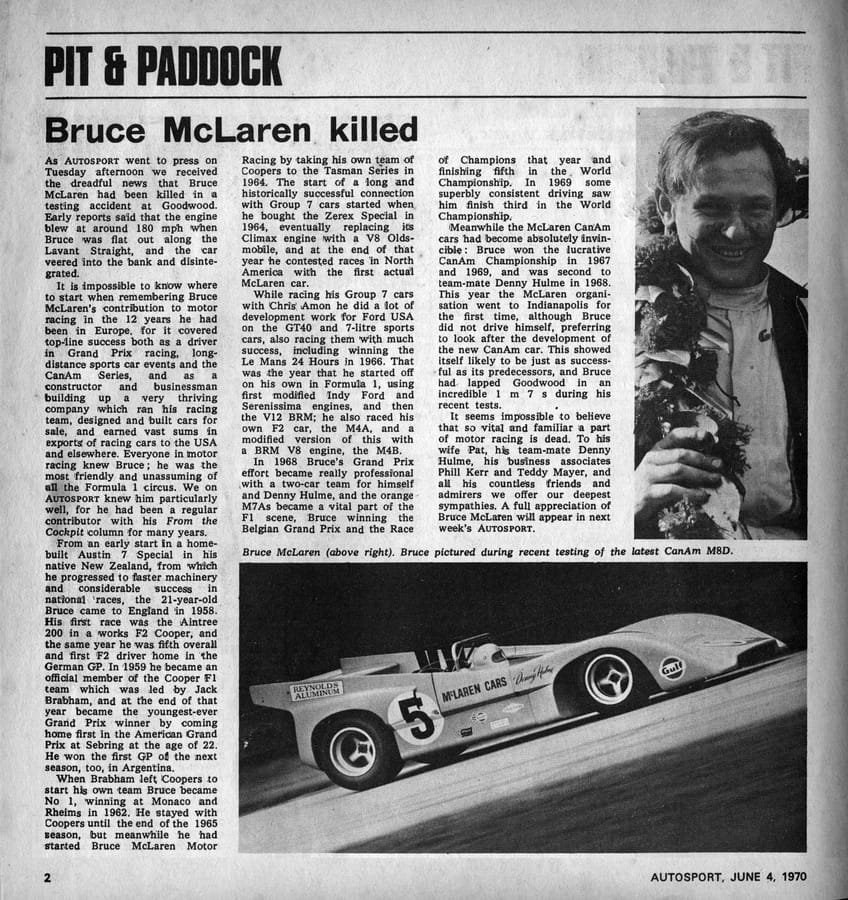

It was during that Tuesday afternoon, as we were closing up the last news pages – called then, as now, Pit & Paddock – that I got the phone call.

Numb disbelief gave way to outrage, and then grief. Bruce was dead. Killed while testing the new M8D at Goodwood.

In a daze I hastily rejigged the first page of P&P, struggling to condense from memory the achievements, and the man, into an inadequate 650 words. The presses rolled on time. Then, throughout Wednesday, feeling desperately sad and confused, I laboured over a 2000-word obituary for the following week’s issue.

It took the tragedy to make us all realise how universally Bruce was loved across the entire motor racing world, which was then admittedly a smaller, much more friendly, less financially stratospheric place. For all the people he had touched, however briefly, Bruce was a very unusual man. And still he is an unforgettable one.

What would he think today if he were to visit the McLaren Technology Centre, or if he saw parked in the street (as I did last Saturday) a metallic dark red 650S with his name on the badge?

His legacy is more than a name: it is a whole ethos. The line from that first Formula 1 race at Monaco in May 1966 to Canada on Sunday week is an unbroken one.