Why does Formula 1 change its regulations?

F1’s game-changing 2026 reboot is the latest in a grand tradition of shaping the sport to suit the era. Here’s why and how they renovate the rules

Read time: 5.5 minutes

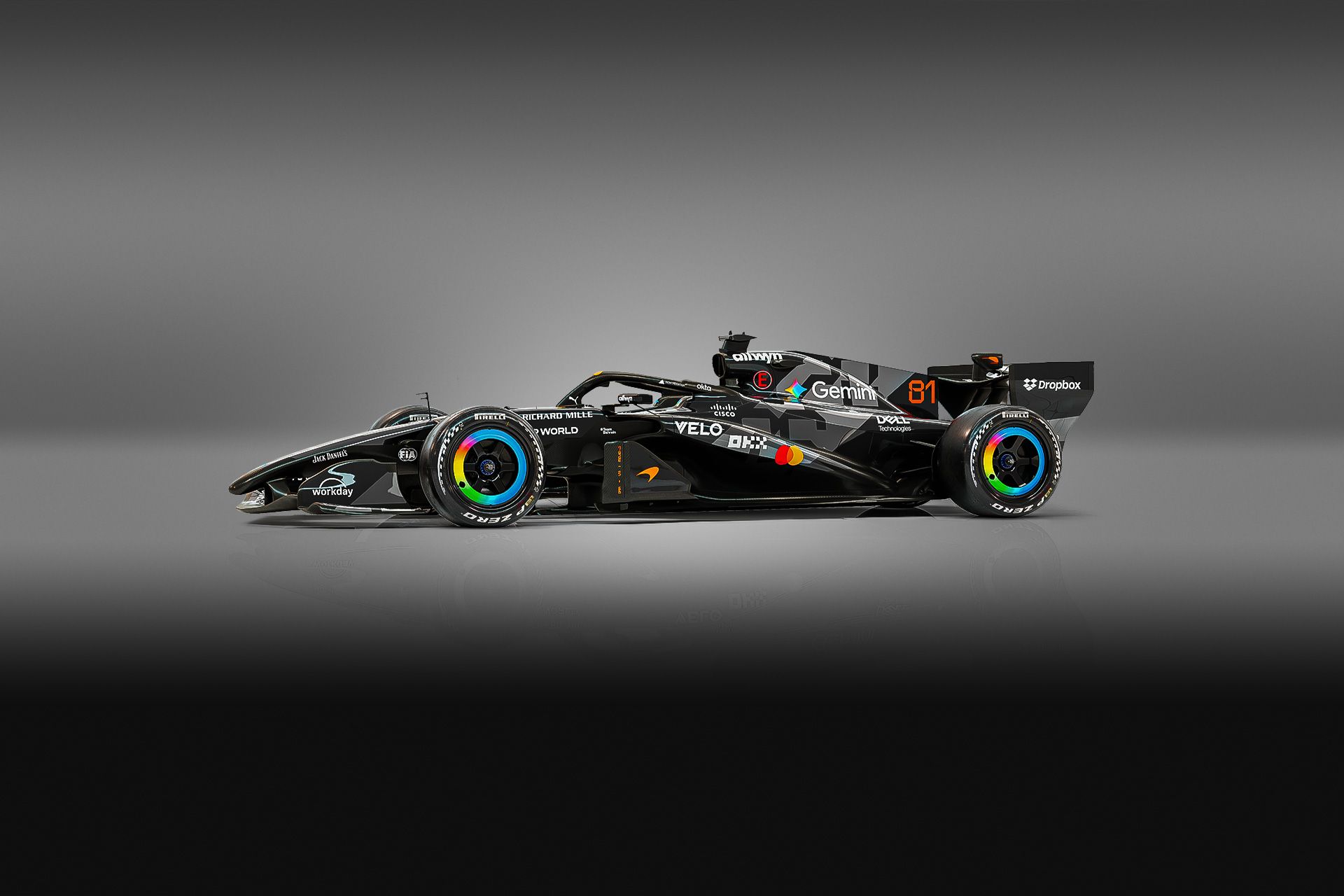

The cars about to launch for 2026 represent a change for F1, the size and scope of which are breathtaking. New engines, new tyres, new chassis rules mean the differences between 2025 and 2026 are unprecedented.… but on the other hand, they’re also pretty familiar.

Since its creation in the post-war period, F1 has continually evolved. Most sports do… but where others tinker around the edges, F1 tends to tear up the manual and start from a clean sheet of paper. Why?

Progress vs tradition

There is friction between progress and tradition, and it exists across the board. F1’s constant pillow-fight with technology doesn’t make it unique in elite sport. From spaghetti-strung racquets in tennis to hot drivers in golf, there is often a fascination with new tech that directly threatens the sense of what the sport is.

Golf has a problem oddly similar to F1: technology improves, balls travel further, and courses are lengthened. When classic venues face a future of being rendered obsolete or changed beyond recognition, that’s when the metaphorical brakes are applied: in the last few years, golf has seen new regulations to limit the volume and coefficient of restitution for drivers, while golf balls are set to ‘rollback’ in 2028 with changes to hardness, core density and aerodynamic lift… which sounds very much like something from our world.

F1 isn’t against cars going faster – providing they can safely be contained. But if speeds go too high, many classic F1 tracks face the choice of either disappearing from the calendar or making expensive wholesale changes to their layouts. Early regulation changes tended to focus on the circuits rather than the cars: demanding guardrails rather than hay bales, keeping spectators back a standard distance, and specifying the provision of sand- and then gravel-traps. Eventually, though, attention turned to the cars, where it remains.

Many methods are used to slow the cars down. The big, generic club is a reduction in horsepower. That’s taken many forms. The original 1980s turbos faced a string of measures to limit their output as speeds cycled ever higher: a 220l fuel tank capacity limit in 1984, then 195l in 1986, then boost pressure limited to 4bar in 1987, and then 2.5bar in 1988. When the turbos were banned, the next two decades saw the displacement of normally aspirated engines gradually reduced: 3.5l initially, then 3.0l in 1995, and 2.4l in 2006.

Chassis regulations to control speed tend to be more subtle and often introduced reactively to counter specific trends. Many branches of motorsport have a rulebook telling car designers what they can do, F1 only specifies what they can’t. It means that F1 designers have historically had a great deal more freedom to innovate… but also a brick-thick rulebook and a great many grey areas. Thus, defining moments in chassis design don’t usually begin with new rules, though they often end with them.

The (original) ground-effect cars of the late 1970s and early 1980s increased downforce significantly but were banned for 1983 in favour of regulations mandating flat floors, because speeds were rising faster than circuits and crash-mitigation technology could contain them. A decade later, a similar thing happened with active suspension and other electronic driver aids: speeds rose rapidly, and regulation stepped in to bring things back under control.

The entertainment factor

While safety always comes first, sport is also an entertainment business – and both of those words are important. Thus, F1 will change the regulations to make the sport more entertaining and more practical. While the history of engine regs tends to focus on reducing – or, at least, containing – horsepower, occasionally the opposite is true. Thus, in 1966, F1 went from a 1.5l normally aspirated engine to a 3.0l version, driven by a desire to retain F1's distinction as the fastest branch of motorsport on track.

A different version of evolution has come to the fore in recent decades. The aero regs introduced in 2009, 2019, 2022, and 2026 have all been tasked with making it easier for cars to race closer together by limiting the scope of the turbulent wake behind a car. In this regard, the individual best interests of teams are at odds with the best interests of the sport: teams will work hard contributing to regulations to prevent, for example, outwashing wakes that make overtaking difficult… and then use all of their ingenuity to circumvent the intention of those rules they’ve just created.

That this cycle repeats is in the nature of the sport: the teams were all heavily involved in our latest set of regulations, which simplify front wings and introduce in-washing bargeboards behind the front wheels, but as soon as those regulations were codified, they started work again to claw back their lost outwash.

The business of sport

There is, of course, also a bottom line to consider. The real seismic shift in the last decade has been the presence of a stable grid. Across the 77 years of the World Championship, more than 100 teams have folded – but none since 2016. Ours remains a brutally competitive sport, but over the last 20 years, there has been an acknowledgement that reducing costs and encouraging stability create a more competitive field.

The in-season testing ban, introduced in 2009, made a huge difference to spending, as did its companion restriction on wind tunnel hours. Smaller changes, like the 2008 regulation mandating a common Engine Control Unit (ECU), followed the same philosophy: costs were reduced without sacrificing the qualities that make F1 popular with fans. It was the success of these changes that paved the way for the introduction of the cost-cap in 2021.

Of course, not all costs associated with regulatory changes come with a price tag. Some are more philosophical. While many regulatory changes qualify as watershed moments, perhaps the biggest came in 2009 with the introduction of F1’s first hybrid technology. The Kinetic Energy Recovery System (KERS) was modest by today’s standards, but the thinking behind it marked a turning point: while F1 engine tech had always exhibited a degree of road relevance, for the first time, a conscious decision was taken to put F1 out in front of expected road car trends. This toe-in-the-water led to the 1.6l V6 hybrid of 2014 and now, the new 2026 hybrid with its 50:50 split between ICE and electrical power.

Changes to the regs like this don’t have an immediate bottom-line impact on the teams, but having road-relevant engine regulations stimulates interest from road car manufacturers, who, in turn, ensure a healthy and competitive supply of engines – at a price the teams can afford.

The entirety of the 2026 regulation changes are huge. Arguably more ambitious than anything F1 has ever previously attempted, it is the cleanest of clean sheets of paper. But these regs contain the same elements of improving safety, delivering practicality and enhancing entertainment that have driven every regulation change over the previous eight decades.

The process

In the modern era, changes to the technical regs tend to proceed at a stately pace. Should the FIA note a safety risk, it can unilaterally introduce an immediate change, but it takes consensus and study to address larger-scale changes, such as the impending 2026 reboot.

Typically, they will assemble working groups from the various stakeholders. Led by the FIA, F1 will be heavily involved, as will the teams and power unit manufacturers, while the FIA will often call on outside expertise to bolster its collective knowledge. As part of this, the F1 teams will be assigned research projects - simply because they have the resources and experience to do the work.

A highly visible and very successful example of this is the Halo, which began with a Frontal Protection Working Group, convened at the end of 2014, and saw Ferrari, Red Bull, and Mercedes take on individual research projects before a prototype was tested on Jenson Button’s MP4/31 during Free Practice for the 2016 Italian Grand Prix. Just under two years later, the Halo was written into the technical regs for the 2018 season.

The 2026 regulation overhaul will have followed a similar, albeit much larger, collaborative process, before the FIA began piecing all of the elements together in their full form. They’ll then be formally written up in a hefty new rulebook, distributed to teams, unveiled to the media, and then ratified by the World Motor Sport Council, long before fans ever see the cars out on track. It’s then up to us to break them back down and devise what their new cars will eventually look like.

To find out more about the upcoming regulation changes and to follow the build-up to the 2026 Formula 1 season, stay close to the official McLaren Racing website, app and social media channels, where we’ll be covering all of the action.

Related articles

All articles

The MCL40 is here: Behind the design and what to expect from McLaren Mastercard’s 2026 challenger

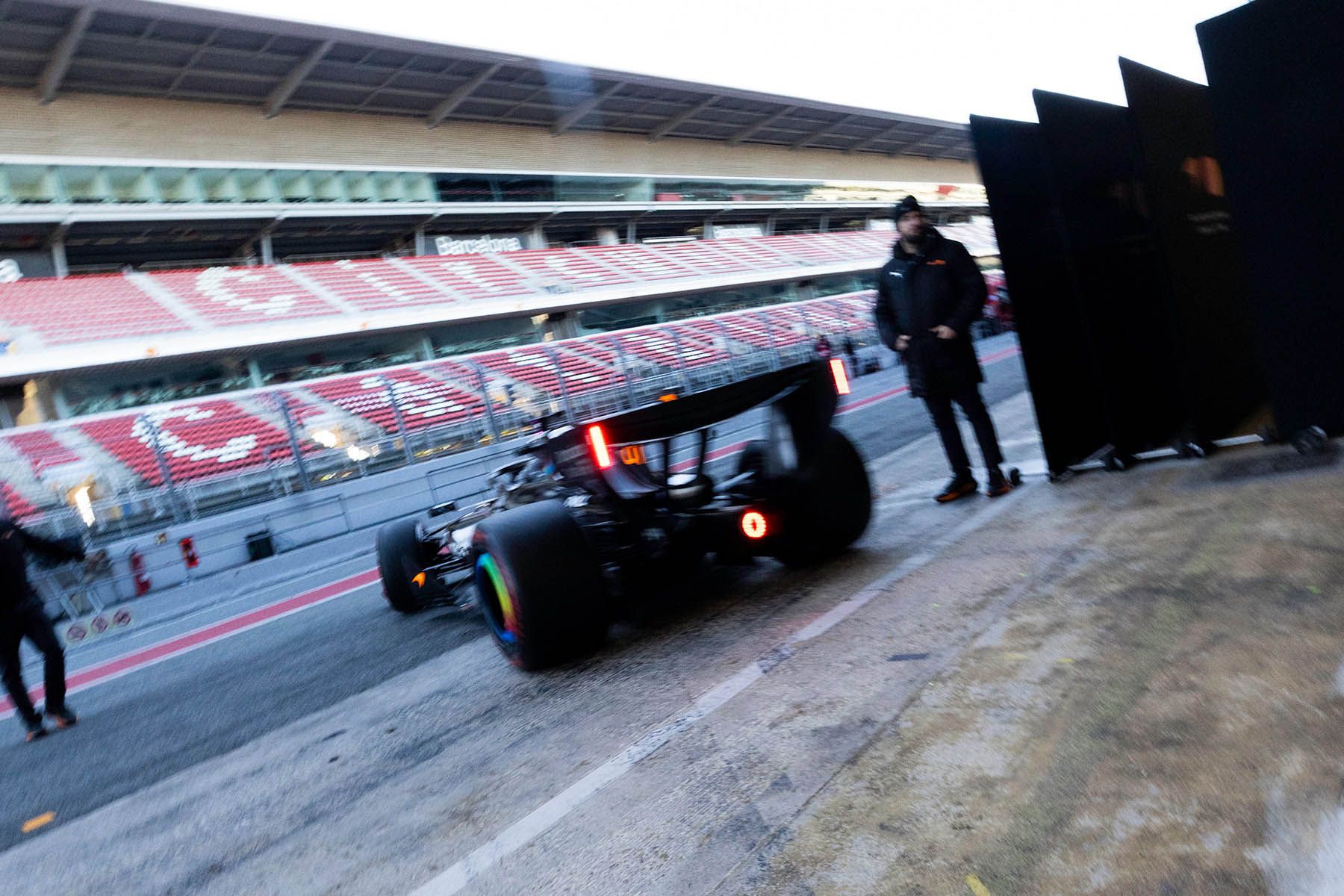

2026 Barcelona Pre-Season Shakedown - Day 3 - McLaren Report

A letter from Zak Brown

A beginner's guide to pre-season testing

Introducing F1’s new terminology

McLaren Mastercard Formula 1 Team and Lando Norris are successful at the Autosport Awards

WATCH: The McLaren Mastercard F1 Team fires up its 2026 car for the first time

McLaren Racing announce McLaren Mastercard Formula 1 Team Reserve Drivers and 2026 Driver Development Programme line up

Explaining F1’s new 2026 regulations: What’s new and what it means

Mastercard and the McLaren Formula 1 Team launch Team Priceless fan initiative for 2026 season

Lando to use No.1 in 2026 as World Champion

McLaren’s history with the No. 1