The Silverstone Collection

Up next McLAREN Racing

23 JulMcLaren Racing Live: London

46 JulF1: British Grand Prix

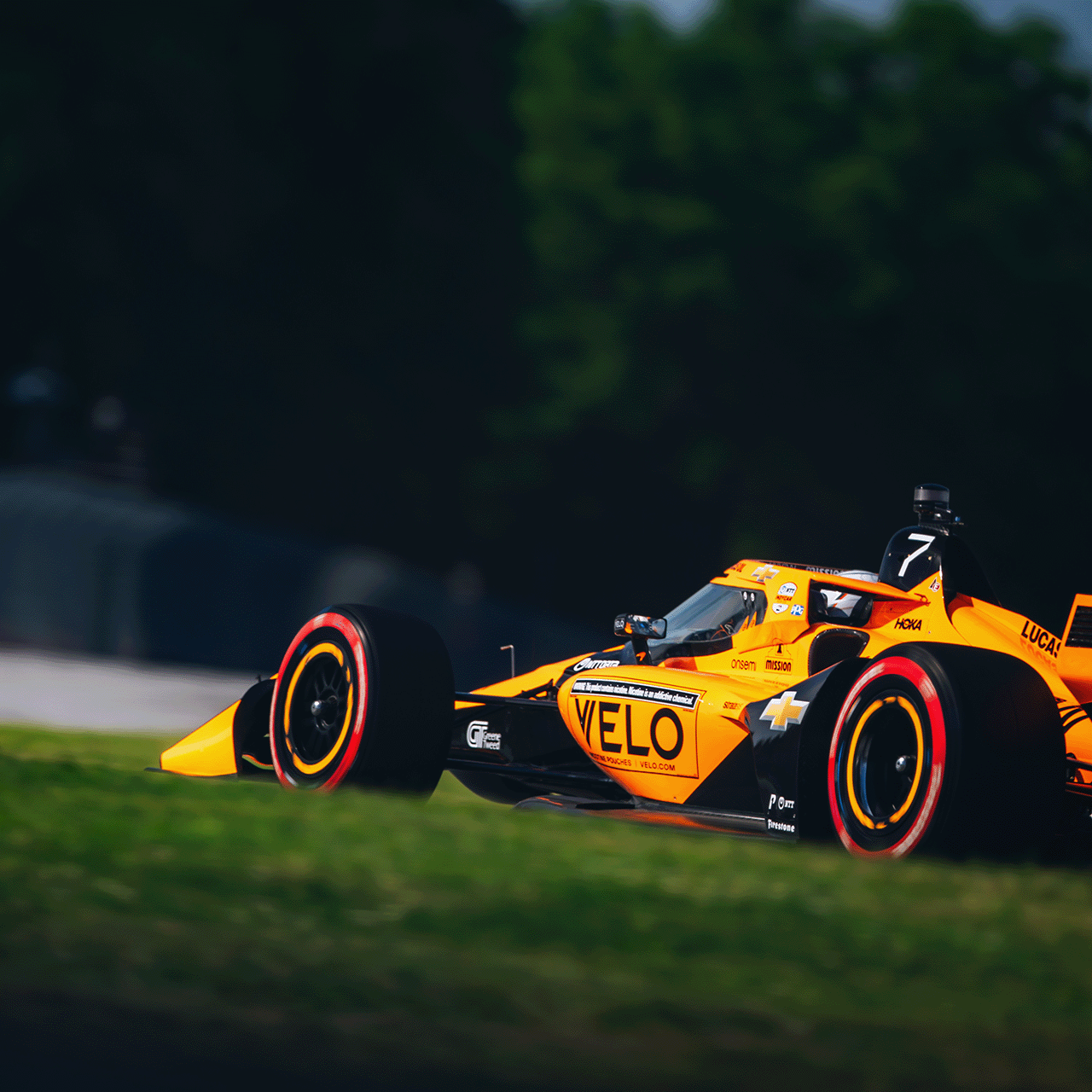

46 JulIndyCar: Indy 200 at Mid-Ohio

1013 JulGoodwood Festival of Speed

1113 JulIndyCar: Iowa Speedway Doubleheader

1213 JulFE: Berlin E-Prix I & II

1820 JulIndyCar: Grand Prix of Toronto

2527 JulF1: Belgian Grand Prix

2527 JulIndyCar: Grand Prix of Monterrey at Laguna Seca

2627 JulFE: London E-Prix I & II

McLAREN Plus

2025

McLAREN Racing Teams

Physical or digital, on track or off road – if it's got four wheels, we'll race it. McLaren is proud to be the only team competing in Formula 1, IndyCar, Formula E, and esports.

We’re back!

McLAREN Racing returns to WEC

30 years on from our historic 1995 24 Hours of Le Mans triumph, it was announced that McLaren Racing would return to the pinnacle of sportscar racing, with a full-time entry in the 2027 World Endurance Championship, racing in the Hypercar class.

We're ready to make our mark on the world endurance stage once again. See you in 2027!

Celebrating our heritage

Discover more

How good actually were McLaren and Lewis Hamilton in 2008?

The most important car in McLaren’s history?

Meet those who celebrated McLaren’s two most recent title wins, 26 years apart

F1's ultimate rivalry: McLaren and Ferrari

How Emerson Fittipaldi won McLaren’s first F1 title on three hours sleep

McLaren’s defining moments in Monaco

Game Changers: Innovations that changed F1

How good actually was Ayrton Senna? Hint: Exceptionally

James Hunt's defining moments

F1’s greatest ever Qualifying lap: Ayrton Senna in Monaco 1988

How Senna and McLaren forever changed each other

The most important day in McLaren's history?

Close-run things: McLaren's closest championship battles

The road to McLaren's F1 debut

Latest news McLAREN Racing

Jake Benham joins McLAREN Shadow F1 Sim Racing Team

"I can't wait to see him working alongside Alfie, Wilson, our engineers and development drivers"

2025 Goodwood Festival of Speed line-up

Celebrating the team’s heritage by running the four iconic cars up the hill

How good actually were McLAREN and Lewis Hamilton in 2008?

Scars, unsolved mysteries, and relentless upgrades: Inside one of F1’s most dramatic seasons

Separating the good from the great

Lando and Oscar on the qualities that define an elite athlete