Meet the race crew

How our crew get the wheels turning for a grand prix weekend

The last of the 60-strong race crew has arrived in Melbourne; more than 40 tons of freight is on-site at Albert Park; food is being cooked; team clothing is being ironed and the atmosphere is building. The season-opening race is within touching distance.

The Australian Grand Prix is the first of 21 races on the 2019 schedule. Over the next nine months McLaren’s race team will zig-zag its way across five of the world’s seven continents; team members will spend more time with each other than they will their families and they will clock up more air miles than most people manage in a lifetime. Proof, if it were needed, that working in Formula 1 isn’t a job; it’s a way of life.

But our employees have the same passion for racing as our founder, Bruce McLaren, who won his first grand prix 60 years ago this year. The game has changed since Bruce’s day, in terms of personnel numbers and car speeds, but the fundamentals of exquisite preparation and beautiful detailing remain the same.

Here, then, is a breakdown of a 2019 race weekend. Wonder what Bruce would make of it?

10 days to go

Travel. Not everyone arrives trackside at the same time. The preparations begin 10 days before the race, when the ‘pre set-up’ crew arrives to build and prepare the pit garage. The fly-away races have the added complication of them needing to deal with 12 tons of sea-freight which, in the case of Australia, left the McLaren Technology Centre (MTC) at the beginning of January.

All of the heavy equipment travels by boat, things like partner panels, work benches and generators. “None of it has a bearing on car performance,” says Team Manager Paul James, “and it’s cheaper to send it by boat than by plane. We have five sets of sea freight, all heading to different parts of the world at the same time. The kit used in Melbourne will travel from there straight to Montreal for the Canadian Grand Prix.”

Once the garage build has been completed, the mechanics arrive in the pit-lane to unpack 28 tons of car-related air freight at the long-haul races, or the fleet of Volvo transporters when within Europe. They have to be meticulous in their handling of the MCL34s and all of their constituent parts because even the smallest of accidents can have ramifications on reliability later in the weekend.

The race engineers arrive trackside a day later, usually on the Wednesday of race week, in order to prepare their run plans for practice, qualifying and the race, and to learn more about any new parts on the cars.

The complexity of the logistics in F1 cannot be underestimated. The travel department writes in-depth itineraries for each travelling member of staff and, where necessary, it obtains work visas - such as in Australia. For that reason, everyone in the race team is required to have two passports: one to travel with, leaving one free to be given to the relevant consulates.

No rest for the wicked?

Sleep. With team members constantly crossing time zones, ever-increasing amounts of research have been invested in sleep patterns. The season opener in Melbourne is 11 hours ahead of the MTC in the UK, which plays havoc with people’s body clocks.

“We’ve done quite a bit of research into this,” says Paul James. “We’ve monitored the sleep patterns of people in the team and we’ve examined nutrition - in fact we’ve looked at pretty much everything to try and combat jet-lag. While nutrition and exercise play a part, there’s only so much you can do, unfortunately!

When it comes to hotels, McLaren is lucky to have Hilton as a long-term partner. They have nearly a million hotel rooms worldwide, which is very convenient for McLaren.

Only at one race, the Belgian Grand Prix, is it necessary for the team to travel more than a couple of miles from the circuit to the hotel. Spa-Francorchamps is in a very rural location in the Ardennes forest, forcing the team to stay at a hotel 50 minutes from the track, near the German border.

The last job to tick off before the guys start work in earnest ahead of the race is the delivery of team kit. At the start of each grand prix weekend team members are given four sets of team clothing and three high-vis t-shirts, which are used during the set-up days. When that’s been delivered, everyone’s good to go.

Build me up, buttercup

Car build day. All of the relevant car components are in the pit-lane by this point in the week, so it’s time to start building the MCL34s. There’s a relaxed atmosphere in the garage and the only goal is to have both cars - chassis, engine and gearbox - complete by the end of the day.

The engineers are on-site as well to monitor the progress of their cars. This year Tom Stallard is overseeing the engineering on Carlos’ car; Will Joseph is the man in charge of Lando’s.

There’s even time for a bit of chat with the team’s neighbours, Haas and Racing Point. Formula 1, for all its ferocious on-track competition, is like a big family and friendships are inter-team as well as intra-team. As it was in Bruce’s day.

The trackside kitchens are also up-and-running. Absolute Taste’s chefs serve three meals a day from their kitchens, which are located at the back of the hospitality suites at long haul races, or in the Brand Centre at European races. Produce is always fresh and bought locally.

Preparation, preparation, preparation

Prep day. The busiest day of the weekend because all of the preparation work has to be completed by nightfall.

It begins with the first fire-up of the week. It’s carried out as soon as the FIA inspectors have cut the seals on the power units, which they do 24 hours prior to the start of Friday’s first practice session. So, if the first session is at 10am on Friday, the seals are cut at 10am on Thursday.

This is the mechanics’ first chance to check the cars’ systems are operating okay following the car build, although they don’t always get the luxury of a Thursday fire-up.

“We had to delay the fire-up of the car at the Japanese Grand Prix last year,” says Paul James. “We’d changed the oil specification and we couldn’t get it to Suzuka in time for our usual Thursday fire-up. It led to an anxious Thursday night, but everything was fine.”

The team also takes both cars to the FIA weigh-bridge at the end of the pit-lane to check its legality. Everything, from wings (which have increased in size this year), to ride-heights and weight (which has also increased), can be measured there.

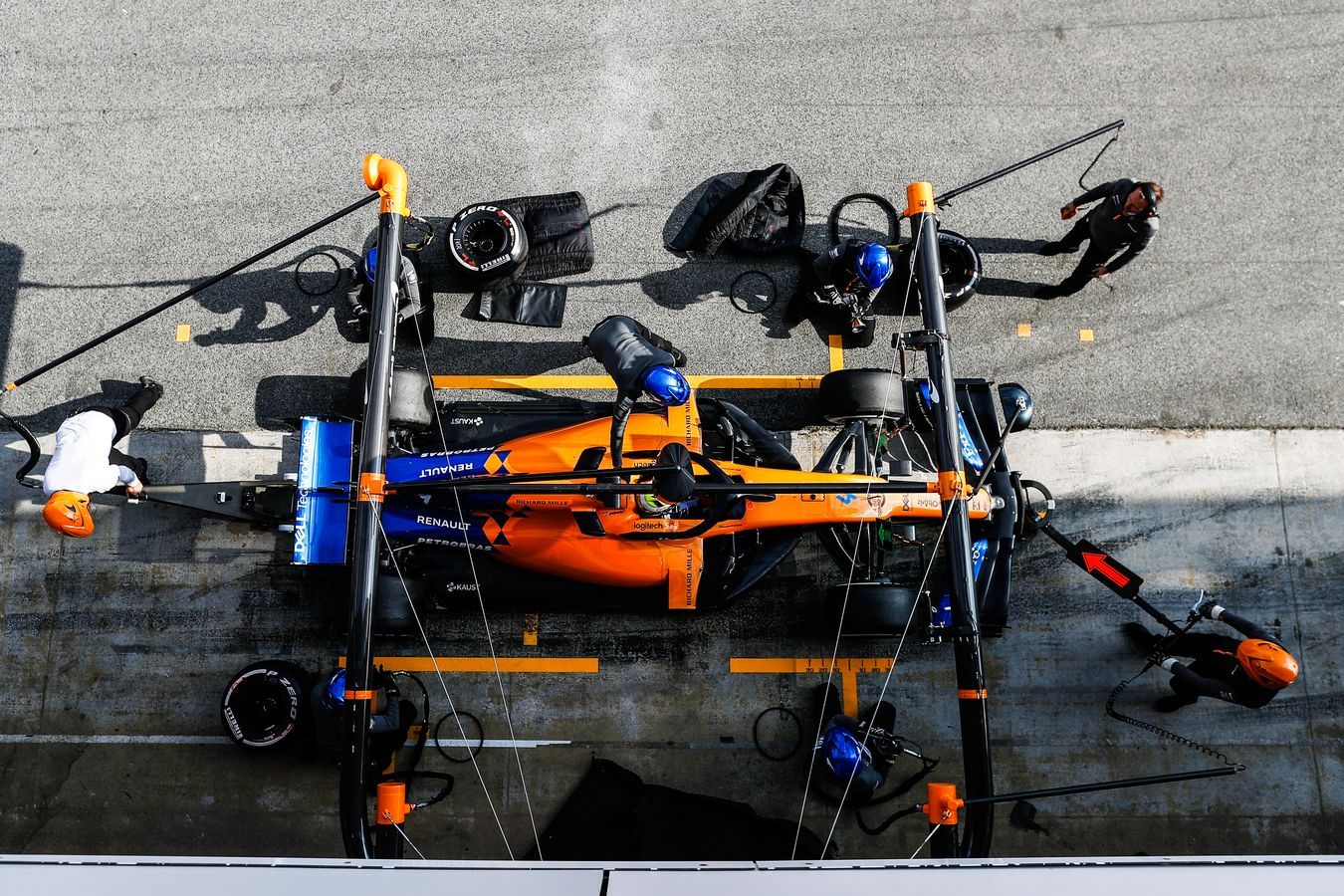

Other Thursday jobs include pit-stop practice. The team does more than 1,000 practice stops in the race bays at the MTC over the winter and they adapt those skills to each pit-lane around the world. They carry out between 12 and 15 practice stops on Thursday afternoon.

For the engineers, Thursday is another prep day. They carry out track walks with their drivers to see what’s changed since the previous year, and they have an in-depth meeting, during which they discuss updates that have been brought to the cars and their plans for each of Friday’s practice sessions.

Practice makes perfect

Practice day. A pressured day. There are three hours of practice - split equally between FP1 and FP2 - after which the mechanics have no let-up because they are working to the curfew, which comes into effect eight hours after the end of second practice. Everyone working on the car has to have left the F1 paddock by that time.

During those eight hours the race gearboxes are installed on both cars and all significant set-up changes are made. The latter isn’t the work of a moment because it takes time for the mechanics to get their instructions from the engineers, who first need to debrief with the drivers and then look through the cars’ data.

To ease the pressure of working to the curfew - which was first introduced by the FIA in 2011 - we have increased the number of mechanics on each car from three to five. But there’s no time to relax because the work has to be carried out faster than in previous eras.

“Prior to the introduction of the curfew,” says Paul James, “we could - and often would - work into the small hours every night. We can’t do that now, so there’s more pressure. But, overall, it’s definitely a welcome addition to the regulations because the guys at least get some sleep now.”

Among all of this, there are still more pitstops to practice. Again, the aim is to do 12-15 stops and the aim this time is to get them all around the 2.5s mark.

Qualifying

Qualifying day. As the weekend progresses, the workload gets easier for the race team. The pressure increases because the team needs to perform faultlessly in qualifying and the race, but the amount of physical work that has to be carried out on the cars decreases.

There are still practice pitstops to be done and the final practice session to carry out on Saturday morning, but once qualifying has finished the ‘parc ferme’ regulations prevent the mechanics from working on the car, unless it has accident damage that needs repairing.

“Post-qualifying is pretty easy for the guys,” says Paul James. “You can’t work on the cars, so they do their usual post-qualifying checks and, unless there’s a problem, they can in theory head back to the hotel in good time. Mind you, what usually happens is that we remain at the track, poring through data until gone 10pm!”

Lights out

Race day. The mechanics’ race morning preparations are inversely proportional to those of the drivers. While Carlos and Lando have lots of media and partner commitments to carry out, the guys in the garage have little to do. They can’t work on the cars, due to ‘parc ferme’, so there’s a bit of a lull.

There are, of course, more pit-stops to practice. They carry out fewer than on previous days, but the goal is to get every stop coming in at 2.5s.

“Sunday is a bit of an awkward day,” says Paul James. “There’s a massive lull to begin with and you have to kind of make yourself up for the race. The guys are tired, after the intensity of the previous days, and so we do a few exercises to wake everyone up as the clock creeps towards the start. Luckily, the adrenaline kicks in when the pit-lane opens and we’re away.”

The race team goes onto autopilot when it’s time to head to the grid. Each person has a specific set of jobs from when the pit-lane opens through until the end of the race.

But while the cars are fighting on-track, the paddock comes alive once again. The pre-set-up crew are back to work, moving travel boxes into position so that the post-race pack-up can start as soon as the chequered flag drops. Usually, everything is done and dusted six hours after the end of the race.

Even with everything packed away, the race doesn’t really end there. It’s a race to the airport to get everyone and everything back to base as quickly as possible, before the whole process starts again ahead of the next grand prix.

“It’s a full-on schedule,” says Paul James. “All of our guys go to every race, unless there are exceptional circumstances, so we try and give them time off in between races. At the end of the season, between the Singapore Grand Prix in September and the end of the season, the mechanics don’t enter the factory. They go straight home to their families between the races and only return to the MTC on 9 December.”

Formula 1 is a nomadic existence. It’s pressured. It’s frustrating. It’s tiring. It’s exciting. And the people at McLaren wouldn’t have it any other way. Just like Bruce.