The search for the extra pedal

"Our ‘brake-steer’ solution worth nearly half a second per lap..."

During the summer of 1997, sharp-eyed Formula 1 photographer Darren Heath spotted Mika Hakkinen’s McLaren with its brake discs uncharacteristically glowing orange in the middle of a corner.

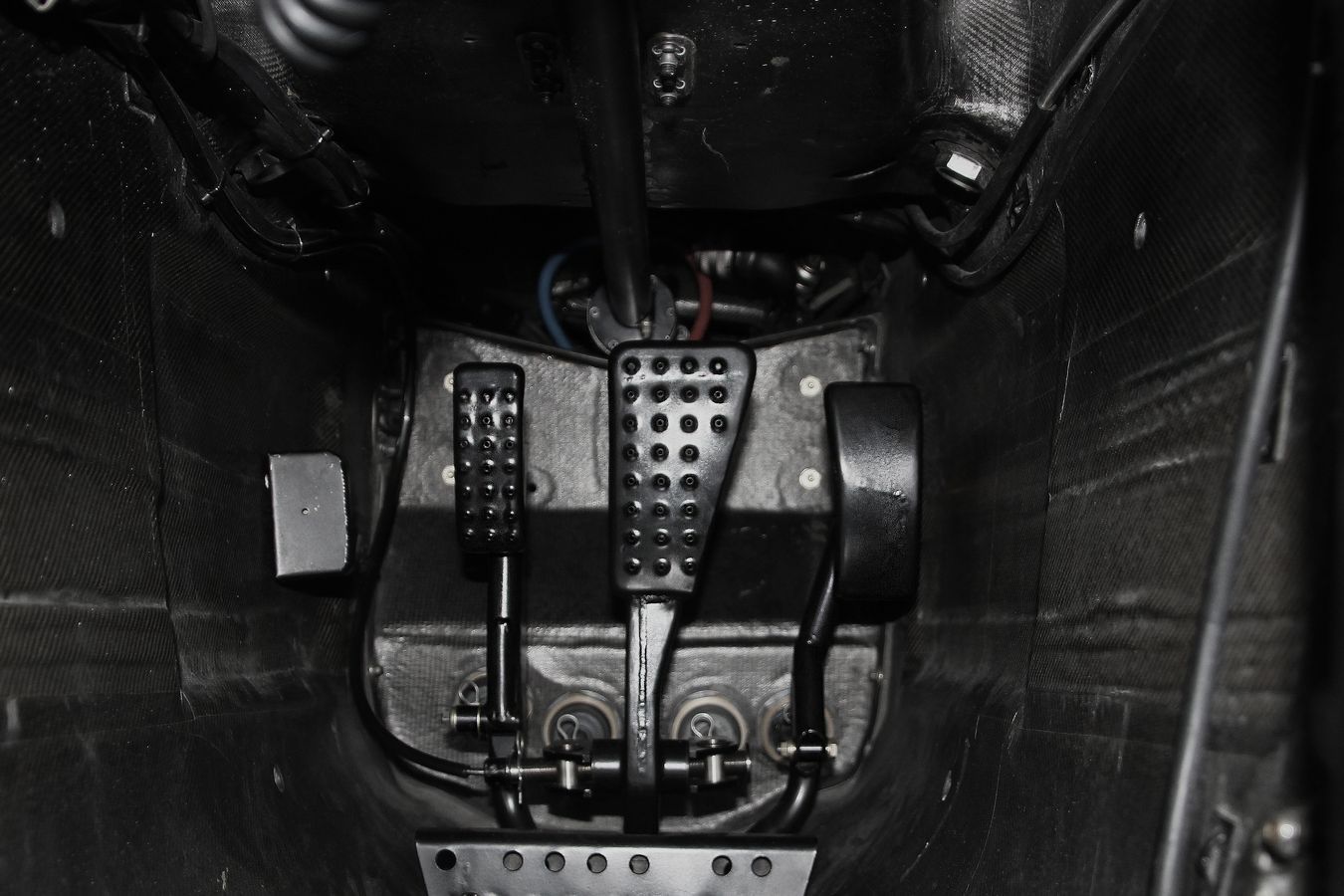

Something about it wasn’t right; Formula 1 drivers don’t brake mid-corner – at least, not if they want to go faster. Heath embarked on a quest to find out what was happening, finally getting photographic proof of an ingenious – and perfectly legal – extra brake pedal hidden in the car’s footwell.

With typical paranoia, rival teams attempted to stem McLaren’s secret advantage, claiming they would be bled dry trying to devise their own unique solutions. McLaren’s braking system would need to be banned, they cried, which it eventually was, but not before it had won several grands prix.

But, as we reveal in full for the very first time, our ‘brake-steer’ solution worth nearly half a second per lap was just a simple piece of kit comprising ‘fifty quid’s worth of parts’ scavenged from the back of one of the race car transporters…

A single, great idea

Every Formula 1 teams spends huge amounts of time and money researching and developing concepts and ideas for its cars and operation. R&D is a never-ending quest for faster lap-times – with the usual caveat that the more money you spend, the faster you go.

However, all the money in the world is sometimes no substitute for a single, great idea – particularly when it solves a particularly tricky problem or provides a neat and nifty advantage. That was the case with the double diffuser used by Brawn GP in 2009, and the F-Duct, which was developed by McLaren a year later – both were clever readings of the rulebook that allowed the engineers to eke out an advantage.

One further famous example was the so-called “fiddle brake”, given its name much later by Ferrari technical boss Ross Brawn, but known within the team as “brake-steer,” that McLaren ran in the latter half of 1997 and into 1998. This simple concept allowed the rear brakes to operate on either the left or right side only, providing a clear benefit under acceleration in corners – and an instant lap time advantage.

A “Eureka!” moment

The idea originally came from veteran McLaren chief engineer Steve Nichols – who literally had a “Eureka!” moment in the winter of 1996.

“It was Christmas time and I was on holiday at my parents’ house and lying in the bath,” the American recalls. “We typically set the cars up with quite a lot of under-steer – at the time we had fairly skinny rear tyres and fairly meaty front tyres – and I had this idea to put a rear brake on in the corners, to sort of dial out the understeer.

“Paddy Lowe was head of R&D at the time, and this would be considered an R&D project. So I told him I wanted to try this thing where we have an extra pedal in the car, and we put the right-rear or left-rear brake on to balance the car. Eventually he sanctioned the project. It sat on the test truck for months waiting to be tested, and finally we’d exhausted every other test item. At 5pm or something, at a Silverstone test, they said let’s try that brake thing!”

The technology was basic, to say the least: “All we had to do was put an extra master cylinder on the car, and a length of Aeroquip [brake hose] that went to the right rear calliper, so that when you pushed the normal pedal it would put both rear callipers on, and when you pressed the fiddle brake it only activated the right rear.”

“It was surprisingly simple to implement,” recalls Tim Goss, who was chief test team engineer at the time. “We obviously had to check that we were clear on the regulation side. My recollection is that we were confident that it was legal, and we just went for it. In terms of how we got to the assembly, and how we applied the brakes to one rear wheel, it was not much more than an additional pedal and brake master cylinder plumbed in the right way.”

Getting it on track

The first man to test it on track in early 1997 was Mika Hakkinen, partly because it was more complicated to fit the prototype to David Coulthard’s car.

“In fact, I had thought of it specifically for David,” says Nichols. “Because he used to say he didn’t like oversteer. I thought this would give him the opportunity to set up the car with quite a lot of understeer, and then balance it with the fiddle brake. He still had a foot clutch because he was an old-fashioned kind of guy! He actually refused to test it, because he thought it was weird.

“Mika was using the paddle clutch so we just went back to an extra pedal – still only three, but throttle, brake and fiddle-brake. He was very open-minded so he went out and tried it, and on his first run he went half a second a lap faster, which was pretty enormous.

“It did a fantastic job. I set it up on purpose with the pressure in the master cylinder so that he had to push quite hard on it, because I didn’t want him to tap the thing and it suddenly spin. He’d use the normal brake to slow the car down enough and then use the fiddle brake just to balance the car. You could push with a little more or less pressure.

“He thought it was great. So then David generated some interest, but he still couldn’t countenance a hand clutch, so then we had to find space for four pedals in his car.”

With the original system, as used for the remainder of 1997, the team decided for each circuit whether to have the left or right rear brake operate, depending on the layout of the corners.

Driving harder and harder

“We were racing with it on just one side,” says Goss. “So we’d pick which side we’d want to do, biased mainly to long high-speed corners where we had understeer. As you applied the brake mid-corner it would brake one of the rear wheels, and as you didn’t want to slow the car down, you’d open the throttle to compensate.

“So it was a combination of pressing on two pedals at the same time. In doing that you’re putting more torque through the outside rear wheel and less through the inside, and that puts a yaw moment on the car to steer the car around the corner. In corners where the car had a lot of understeer, then if you applied the brake steer, you would reduce the understeer.

“As the drivers got more used to it they could drive the thing harder and harder, which reduced the understeer. You had the added benefit that you didn’t have to carry so much front wing on corner entry, so you ended up with a more stable car.”

Coulthard soon became a fan, and he was quickly up to speed with it.

“It was a brilliantly simple piece of engineering, which worked,” says David. “It meant I had four pedals because I didn’t use the hand-clutch. Well, I had a hand-clutch – actually I had two hand-clutches, and one foot-clutch, which I preferred. I felt at that time it was still an advantage.

“I had tried left-foot braking in the ’96 car in Jerez and didn’t really feel comfortable with it, and reverted to right-foot braking. And it must have been 1999 before I got into left-foot braking again.

“We had to learn how to work with it, because you had to accelerate while you braked, otherwise you just locked the wheel. You could feel it was an advantage, because it yawed the car. So instead of riding over the front tyre, you could rotate the car without having to put steering lock on.

“And steering lock affects the aerodynamics quite a lot, so there was an advantage aerodynamically in having that. We could use it also to control a bit of wheel-spin on the inside wheel, coming out of tight corners. Independently Mika and I both worked that out. The theory had been proven in tanks and things like that, but actually doing it at speed out on the track was always going to be a bit different!”

Journalistic intervention

Initially rivals didn’t know what McLaren was up to – until a good bit of investigative work was done by the media.

After the Austrian GP, F1 Racing magazine photographer Darren Heath was going through his shots from the race weekend back at the office – this was the pre-digital era, so he had to wait for his rolls of film to be developed.

He was surprised to see that shots of both McLaren drivers showed a rear brake disc glowing at a point where the cars were under acceleration out of a corner. Together with editor Matt Bishop – later to become an employee of McLaren – they pondered possible explanations.

It was Heath himself who thought that some kind of extra brake was being employed, and together with Bishop he resolved to try to get a shot inside a McLaren cockpit. And that meant waiting for one of the cars to retire on track, and be abandoned by its driver.

The next race was the Luxembourg GP, at the Nurburgring, and Heath even arranged that Bishop, watching on TV back in the UK, would call his mobile phone if a McLaren retired – and tell him where it was parked.

With incredible timing both McLarens did retire from the race after running at the front, ironically during an ad break back in the UK. Even without Bishop’s help, Heath managed to get to the cars. Coulthard had left his steering wheel on, so Heath couldn’t get his camera and flashgun into the cockpit, so he didn’t snap the Scot’s four-pedal arrangement.

However, Hakkinen had taken his wheel off, so Heath was able to fire off a few shots, with guessed exposures, and get shots of the foot-well. And when the pictures were developed they showed a little extra pedal in a car that should only have had a throttle and brake.

It was a brilliant piece of clever, investigative journalism – and a fantastically memorable scoop.

The secret gets out

Much to the frustration of Ron Dennis, who initially suspected foul-play until he learned that the pictures were taken on track, the secret was out. Rivals tried to work out exactly what McLaren was doing – and whether it was legal or not.

For the 1998 season the team ran a slightly more advanced version, which allowed the drivers to choose which brake would operate on a corner by corner basis.

“It would have been illegal to have it be automatic,” said Nichols. “But we had a little switch for left and right, so all the drivers had to do was select it. They were complaining a little bit about that, but considering what they have to adjust these days, it was pretty minimal.

It was more work for the drivers, but Coulthard says he adapted quickly: “It was a switch to choose left and right, and an additional pedal,” DC recalls. “Racing drivers, if they have to sing the Russian national anthem backwards while juggling grenades, and it gives them a tenth, they would do it! The competitive animal that you are, nobody would say something is too difficult if it gave you performance.”

Rivals up in arms

Unfortunately for McLaren, rivals were lobbying for the system to be banned, without actually understanding how it worked. The normal procedure was to suggest ideas to the FIA, in a kind of fishing exercise, in order to test the limits of what was legal or not.

“Nobody cottoned on to what we were doing.” says Nichols. “Williams punted something into Charlie Whiting that was all electronically controlled where they would turn off all the brakes except say the right rear, and just apply that one. And Charlie immediately said, ‘No, I think that’s going to be kind of unsafe!’

“Various people were putting in various proposals. Ferrari claimed it was four-wheel steering, they sent the FIA pictures of tanks where they brake one track and that’s how they steer, but they still didn’t know what we were doing.”

In the end, the rival teams’ approach hit the right target, and McLaren’s system was banned early in the 1998 season.

“It was banned on the basis of four-wheel steering, although obviously it was not realigning the wheels,” says Goss. “We called it brake-steer, which was unfortunate when we tried to argue that it wasn’t anything to do with steering! It was a bad choice of name from ourselves. Then Ross Brawn coined the term “fiddle-brake” which is used by cross-country trial cars for a handbrake that works on each of the rear wheels to try and turn the car.”

For McLaren and Nichols, the decision was a source of disappointment.

“I remember Alain Prost, who had a team at the time, saying we’ve got to ban this because it will cost millions in development,” he says. “And it was fifty quid’s worth of parts that we already had in the truck!”