McLAREN's IndyCars

The return of one of our original papaya cars sparked some Brickyard memories

McLaren maintains an impressive collection of historic racing cars, representing all eras of the company’s history.

The latest addition to the fold is a very special one. The car with which Johnny Rutherford won the 1974 Indianapolis 500 has returned after spending years in private ownership, including a spell on display at the Speedway’s famous museum.

Now on view at the MTC, it provides a timely reminder of the heritage of the papaya livery that returns to the F1 grid this year, as well as reflecting McLaren’s history of engineering excellence.

McLaren first entered the Indy 500 in 1970 with Gordon Coppuck’s curvy M15. Although new to oval racing, the team was already well known in the USA through its Can-Am involvement. However, while the cars were admired for their design and construction, even winning an award, the results were modest.

Chris Amon was not an oval fan and eventually decided not to compete, while Denny Hulme was injured in a fire in practice. In the race itself, replacements Peter Revson and Carl Williams were out of luck, although the latter finished ninth.

“We didn’t really understand the place a lot to begin with,” recalled former McLaren Indy team boss Tyler Alexander, “And it was a huge struggle. We relied on some information from some people who were there, who were involved with us. They certainly helped, but it all came a little bit at a time.

“We needed to prove ourselves, and then they’d offer us some information, which didn’t help for a while. But after the first year there we felt amongst ourselves that if we could get the goddamn thing to finish, we could win the race.”

The terrible shock of Bruce McLaren’s death came just a few days after the Indy 500 debut. The team subsequently regrouped under Teddy Mayer, and gained more oval experience later that year competing in the other big 500-mile events at Ontario and Pocono.

Coppuck embarked on a brand new design for 1971. The M16 (or M16A as later versions caused it to be known) borrowed its wedge shape from the Lotus 72 which had proved so successful in Grand Prix racing in 1970, taking Jochen Rindt to a posthumous World Championship title. Coppuck felt that the 72’s sleek lines would be ideal for Indycar racing, although the M16 was very much a McLaren design.

“There was a lot more to it than that, you can’t just copy it,” he says. “There were many features unique to the car.”

The M16 was unveiled at the Colnbrook factory in January 1971, some four months before action got underway at Indianapolis. As was standard in those days, it used a 2.6-litre Offenhauser engine, mated to a Hewland gearbox, but with three speeds instead of the two usually favoured at Indy – the idea being to provide better acceleration out of pit stops.

The front of the car produced a lot of downforce, which was balanced by a rear wing that was neatly incorporated into the engine cover, and which cleverly skirted the rules of the time. The car helped to kick start an era of huge wings at Indy, which led to a massive increase in lap speeds.

Meanwhile Roger Penske abandoned plans to run a Lola and had instead become McLaren’s first Indycar customer entrant, with Mark Donohue heading the team’s efforts,

“It meant that the build got a bit more sensible in terms of costs,” says Coppuck. “Teddy was very unsure in terms of how the financial stability was going to be without Bruce. Bruce was so charismatic you always felt that somehow or other he would attract attention. Teddy didn’t have that to work with.”

When practice for the 500 started in May, Donohue and Revson set the pace, and left rivals scratching their heads. Indeed Revson ultimately took pole at a record speed, with Donohue earning second place and Hulme – never a fan of ovals – in fourth. With three cars at the sharp end, a strong race seemed assured.

“When we went to Indy we were very, very pleased to have raised the speed by about 10mph,” says Coppuck. “Peter sat on pole, and considering that we’d only done two Indy races in the history of the company that was a big deal.”

In fact the 500 itself proved somewhat disappointing, with Revson managing only a low-key second behind the Colt of Al Unser, Donohue stopping with gearbox problems, and Hulme spinning early on before having engine trouble. Nevertheless, McLaren had made its mark.

Donohue’s parked machine was badly damaged when struck by a crashing car later on, and a new chassis had to be built and shipped to the USA. He duly won at Pocono and Michigan and led at Ontario, only to retire from the latter when he ran out of fuel after a signalling mix-up. The M16A was undoubtedly the class of the field, and both Penske and McLaren now had their eyes fixed firmly on unfinished business at Indy in 1972.

Coppuck upgraded the basic design for the new season, and the M16B featured a range of modifications. Penske bought two of the new cars, for Donohue and Gary Bettenhausen. The customer team’s year started well when the latter won the second race of the season at Trenton in an older M16A.

However, the real prize was Indy. By now everyone had big wings, and the McLarens were beaten to pole. But Donohue and Revson were again on the front row, in second and third.

Running a conservative strategy which was easy on the engine Donohue survived what turned into a race of attrition. He led the final 13 laps to give both McLaren and the Penske team their first Indy 500 victories, while earning a $218,000 first prize. There was disappointment for the works outfit as both Revson and his team mate Gordon Johncock retired, while Bettenhausen also failed to finish in the other Penske entry.

Not long afterwards Donohue was injured while testing the team’s Can-Am Porsche 917, while later Bettenhausen was hurt in a sprint car crash.

The works team only contested the big 500-mile races, and was also out of luck, although Johncock led at Pocono. However in another race of high attrition at Ontario, the relatively unheralded Roger McCluskey emerged to win for the American Marine team with his ex-works M16A.

Donohue returned for the last couple of races with the trusty M16A, finishing second at Trenton and taking pole at Phoenix before retiring.

Lessons learned with the M16 series would actually feed back into the M23 F1 car that was designed at the end of 1972, especially with regard to making the chassis light.

Meanwhile, McLaren built six revised M16Cs for 1973, for works and Penske use, and the team’s withdrawal from Can-Am ensured that the Indycar programme was the main focus of the US operation.

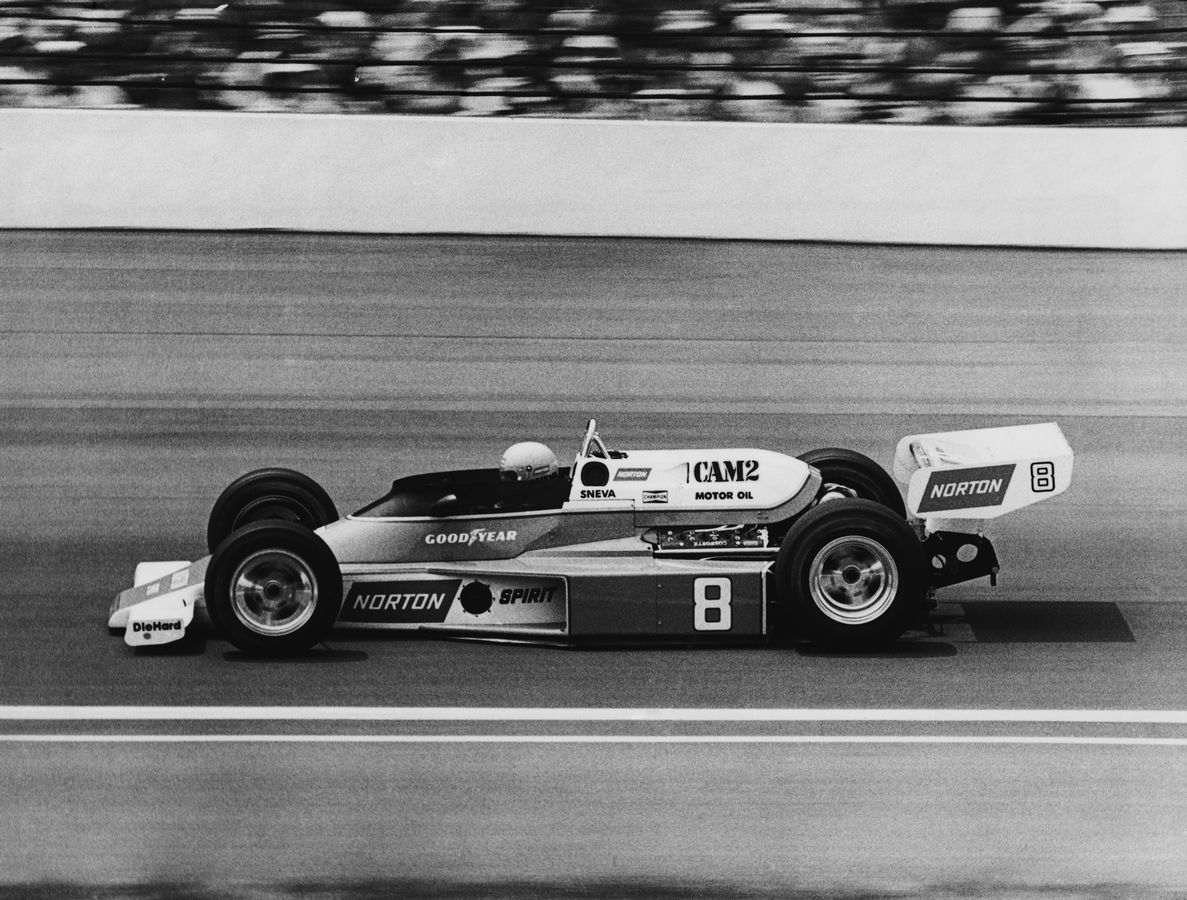

By now rule makers USAC had basically said that anything went as far as wings were concerned. The M16C looked a little more like an F1 machine than the previous car, with a full length engine cover, and a new, more rounded cockpit surround. The works team signed Texan Johnny Rutherford to run alongside Revson, establishing a relationship that would prove to be hugely successful.

Rutherford had a disappointing Indy 500 in 1973, but he won events at Ontario and Michigan, and placed third in the championship. Meanwhile Bettenhausen trumped in the Texas 200 with a Penske-run M16C.

Earlier versions of the car would continue to race in private hands for several years. Indeed in 1973 McCluskey finished third at Indy in his M16A, later winning at Michigan and taking three second places. Against expectations he ended up as USAC series champion with a design that was essentially now two years old.

The 1973 season was a dramatic one, with speeds rising and a series of spectacular accidents in the month of May rocking the sport. USAC opted to slow the cars for 1974, mandating narrower wings and restricting their overhang. Fuel tanks were also made less vulnerable, and there was more of an emphasis on economy.

McLaren updated its existing design to the new rules, and called it the M16C/D. Now it really began to look like the sister M23, with a similar, shorter nose and a chunky rear wing mounted on a centre pylon rather than the earlier strut arrangement.

Also new for 1974 was the absence of the Gulf sponsorship that had proved so successful in the Can-Am era, but the works cars initially continued in the familiar papaya orange livery.

That winter McLaren’s Indy talisman Peter Revson left the team to join Shadow for F1, and Penske for Indycars. Sadly he was killed at Kyalami in March.

It was to be a great year for Rutherford, who was now clear number one at McLaren. He won an Ontario heat early in the year, and then, from a lowly 25th on the grid, he scored a memorable first Indy 500 win for the works team.

Just a week later he won again at Milwaukee. Another victory at Pocono helped him to second in the USAC championship, although he lost the title to Bobby Unser.

Meanwhile Briton David Hobbs finished fifth at Indy in the second McLaren works entry, which ran in Carling Black Label colours.

The M16 series was clearly still competitive, and thus, as with the M23, for the time being McLaren saw no reason for a radical overhaul. So for 1975 the team produced yet another variation on the theme, dubbed the M16E. This time much of the work was done by Coppuck’s young assistant, John Barnard. Penske opted to stick with its proven C/Ds, which the team itself had updated, so only the works outfit had the new cars.

Rutherford enjoyed another good run at Indy, finishing second in a race cut short by rain. His only race victory came at Phoenix, but he again finished second in the championship, this time to AJ Foyt.

In 1976 McLaren continued with the final E version of a type that had already amassed an extraordinary history, with the newer works cars by now joined on the grid by many earlier models which had moved onto private hands, with varying degrees of success.

Rutherford duly won Indy for a second time, as rain cut the race distance to just 255 miles. He added successes at Trenton and Texas as – for the third time in a row – he was runner-up in the championship, losing out to Johncock. Mario Andretti took time out from his Lotus F1 commitments to drive Penske’s M16C/D at Indy, where he set the fastest qualifying time, albeit on the second weekend, so it didn’t count for pole.

The car was still competitive, but just as the M23 was about to be replaced by the M26, so the M16 series was coming to the end of its competitive life. For 1977 it was superseded by the much more modern M24, which was itself derived in large part from the M23.

The change also coincided with a move from the venerable 4-cylinder Offenhauser engine to the new Cosworth DFX, while sponsorship from First National City meant the end of the famous papaya orange colour scheme.

Rutherford got off to a great start with the M24 in ‘77, winning its second race at Phoenix, and leading at Trenton. Alas, he was the first retirement with an engine failure at Indianapolis, where Tom Sneva put his Penske M24 on pole, and finished second. Rutherford bounced back to win three more races.

He had another frustrating Indy 500 in 1978, and was classified only 13th after a troubled race. Later he won at Michigan and Phoenix, and took a string of second places.

By 1979 Indycar racing was in a state of flux, thanks to a split between USAC and the new CART organisation. McLaren went with the latter group, and Rutherford gave the works team its final two wins at Atlanta in what was otherwise a disappointing year – he finished a distant 18th at Indy after losing a ton of time with a gearbox issue.

Facing a lack of sponsorship, and with the F1 team struggling and needing the management’s full attention, McLaren did not compete in Indycars in 1980. Rutherford meanwhile went off to drive the Chaparral, designed by former McLaren man Barnard. By the end of that season Barnard found himself back at McLaren – this time designing a new F1 car…

Meanwhile Coppuck is pleased to see the 1974 500 winner back at McLaren’s base, albeit in Woking rather than where it was born in Colnbrook. It’s a model that means a lot to him.

“It always touches me because, with the Can-Am cars, people expected us to win. But this was the first time that we’d really started to upset the applecart. And it then gave everybody the confidence to do the M23, which won two World Championships.”