Lord of the Ring

Maverick. Playboy. Iconoclast. But why wasn't James Hunt revered as a genuinely fast racer?

The eight poles in his championship season are evidence that the Brit was quick, but it's his pole position at the legendary Nürburgring that cements his status as one of F1 racing's all-time fastest drivers...

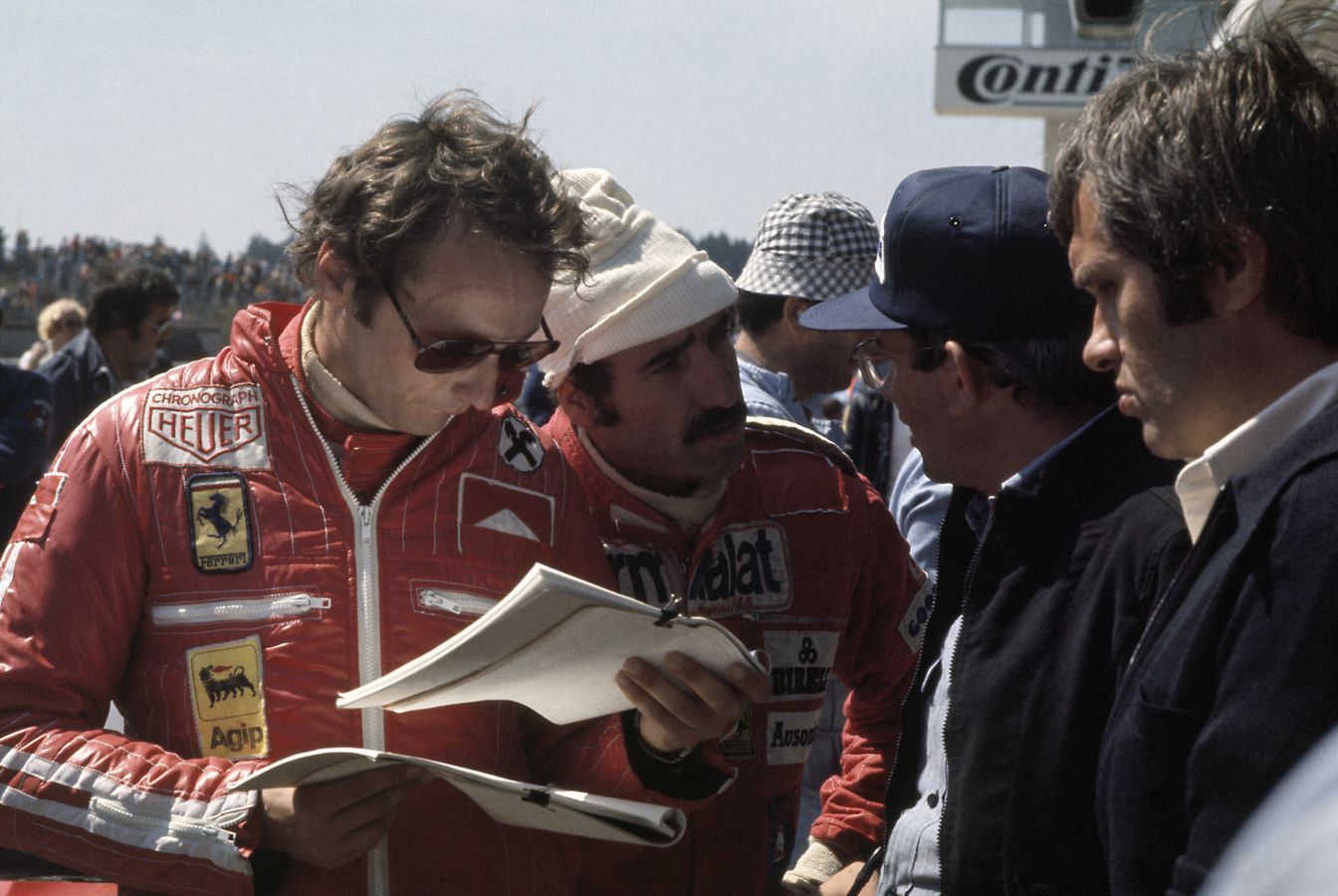

The 1976 season is well remembered for the politics off the track, Niki Lauda’s accident at the Nürburgring, and the wet finale at Fuji which saw James Hunt claim the World Championship in dramatic style. It’s a story that was told so well by Ron Howard in the movie Rush.

However, what is sometimes overlooked is the sheer pace that Hunt showed over the course of the season as he stepped up to the plate and grasped the opportunity offered to him by McLaren.

If James Hunt is remembered as a hard partying, hard racing playboy, he at least deserves to be remembered as a genuinely quick driver – and at a time when grand prix racing was hugely dangerous.

Indeed, he qualified on the front row 11 times in 16 races during that legendary 1976 season, his tally including eight pole positions. And perhaps no single lap was more significant than the one that earned him pole position for the German Grand Prix at the daunting Nürburgring – and proved beyond all doubt that he was made of the right stuff.

Getting the chance of a lifetime

Hunt’s chance to drive for McLaren arrived out of the blue in November 1975 when Emerson Fittipaldi decided not to stay for the following year, and go instead to his brother’s Copersucar team. McLaren needed a replacement in a hurry. Hunt, on the market after his team boss Lord Hesketh decided to cut his losses and pull out of the sport, was the obvious choice.

Although he’d won the 1975 Dutch GP with the upstart Hesketh team, Hunt had never sat on pole. He’d qualified second twice – at Watkins Glen in 1974, and the Osterreichring the following year – and no one doubted that on his day, he was fast. But he’d not had a chance to prove that he was consistently quick. However, armed with the McLaren-Ford M23, he would raise his game in dramatic fashion in 1976.

Lauda was of course the benchmark at the time. In 1974, his first season at Maranello, the Austrian had earned nine pole positions, and he repeated that feat in ‘75, on his way to his first World Championship. Heading into the ‘76 season he was without a doubt the man to beat. And yet at the first race in Brazil he found himself sitting on the grid in second place, having lost pole to Hunt.

It’s difficult to appreciate in retrospect what a significant achievement that was for James on his first outing with his new team. McLaren had only rarely been in the fight for pole in the preceding years. Fittipaldi had earned two top spots in his championship year in 1974, in Brazil and Canada, but none at all in 1975, although he did start second twice.

Hunt’s new team-mate Jochen Mass had never qualified higher than fifth in ‘75, and indeed had often started from outside the top 10. So the M23 was not widely regarded as an out-an-out fast car over one lap, and certainly not compared to the Ferrari 312T.

Hunt still had to convince everyone in the McLaren camp, and the outside world, that he was worthy of the job of replacing double World Champion Fittipaldi. Indeed, some observers had expected Mass to step up into the role of team leader.

First place ahead of the first race

James had other ideas, although things didn’t get off to a great start at Interlagos when he struggled to get comfortable in an M23 that had been honed around Fittipaldi’s requirements.

“The big problem is that when you sit in a car in the workshop you can get everything roughly right, but there’s no way you can get it exactly right until you reach the race track. When we got to Brazil it was all wrong, of course.

“It didn’t fit me, the steering was too heavy and I didn’t like it, so the first day of practice was spent getting the car right for me to drive, and we did nothing at all towards getting the car set up and sorted for the circuit.”

Despite that he was still fourth quickest on the Friday, behind the Ferraris of Lauda and Clay Regazzoni – and the surprisingly fast Copersucar of local hero Fittipaldi.

For Saturday the team made changes to ease the steering and enlarged the cockpit surround to make it easier for James to manoeuvre. It paid off, and towards the end of the final qualifying session he went top. Lauda just had enough time to respond, but an engine failure for another driver in front of him put paid to that. Hunt had made his point, not least to his own team.

“It was also important psychologically because we immediately had each other’s confidence and respect,” he would recall.

Getting the job done

The stellar performance on track also helped the team accept Hunt’s seemingly casual approach to the job of being a Grand Prix driver, which belied the steely determination underneath: “It was not what they had been used to with Emerson,” he noted.

“If you behave ‘badly’ in terms of what is traditionally good behaviour, nobody minds when you are doing well. But as soon as you are not doing well they point the finger at you and say ‘that’s the reason.’”

Significantly Hunt also proved to himself that he could get the job done given the right tools.

“The most important thing in life is to know yourself and know your limitations,” he would explain. “While I felt confident that I could do the job I am trying to do – by which I mean be the best – I hadn’t done it by then, so I had no right to feel that I could. And at that level you can only hope that you are right.

“If you want to be ridiculous about it, I wasn’t to know if the Hesketh was a car that was three seconds a lap better than anything else and I was just driving it slowly, or vice versa – that it was three seconds a lap worse than anything else and I was driving it mighty quick. You can form opinions, but you don’t know for sure.”

The race in Brazil didn’t go well for Hunt, and he eventually retired after a stuck throttle sent him off the road. However, he repeated his one-lap form in South Africa by taking another pole, although in the race he lost out to Lauda. Meanwhile, Mass soon found himself relegated to number two status as Hunt’s superb form continued.

“It was unexpected what happened,” the German recalls. “Don’t forget that March had chucked him out because he wrecked too many cars, and it was not that he was really quick over one lap at that time. He was not the wonder-boy like Roger Williamson, who was fabulous. In Formula 3, James was never that strong.

“But now he was quick. He was doing a lot more testing, so I didn’t work as much with the car. I don’t want to make any excuses here, but it's the way it was. I was a little bit too easy with everything. I thought, ‘Let’s see, it will sort itself out,’ and so on. It did, but against me.”

All about Hunt vs Lauda

One of the most dramatic F1 seasons in history was now well underway, and it was soon obvious that it was all about Hunt and Lauda. After crashing out in Long Beach James bounced back in Spain by taking his third pole in four starts and scoring his first win for McLaren – only to be disqualified because the car was deemed to be fractionally too wide.

There was more frustration in Belgium, Sweden and Monaco as the team briefly lost its way, but at Paul Ricard in July McLaren and Hunt were back on form. James took another pole and this time there were no question marks over his victory.

To his disappointment, Hunt had to settle for second on the grid for his home race at Brands Hatch, and following the infamous first corner accident and race stoppage he won the restarted race on the road, only to be disqualified later.

The next race was the German GP at the Nürburgring, the toughest test for man and machine on the calendar. James had raced there only twice, retiring with mechanical failures in the Hesketh in both 1974 and ‘75, having started from 13th and eighth places respectively.

There was little in that modest record to suggest he was a ‘Ringmeister,’ the nickname accorded to drivers who had shown something special around the daunting 14-mile track.

The Nürburgring had long been a focal point for safety discussions, and it had even briefly dropped off the calendar in 1970, to be replaced by Hockenheim. Drivers had been appeased by improvements to barriers and so on, but there were still doubts, especially concerning the ability of the organisers to properly marshal the full length of the track.

The debate was ramped up further by Lauda, who made his feelings clear in an interview before the race.

“My personal opinion is that the Nürburgring is just too dangerous to drive on nowadays,” he said. “On any of the modern circuits if something breaks on my car I have a 70/30 chance that I will be alright or I will be dead.

“Here, if you have any failure of the car, 100% death! We’re not discussing if I make a mistake, but if I have a failure on the car.”

He wasn’t the only driver to express such thoughts, but in the end it was business as usual, and the German GP weekend went ahead.

“Whether they’re frightened of the ‘Ring or not, everybody wants to win there,” Hunt would say after the season. “Our main problem is that people think drivers don’t want to race there, but that’s not true. What we say is we don’t want to drive there unless it is up to the safety specifications of every track we race on.

“So we have the problem of making sure the track is safe, but we also have a political problem too because when we ask other tracks to do safety modifications for us they can say, ‘Look, you go and race on that bloody Nürburgring without those precautions – why should we bother?

“I didn’t particularly want to race under those circumstances, but politically I felt it was the right thing to do because the drivers’ safety committee did give the race organisers a three-year deal that included 1976.

“If we backed down, our credibility would have been seriously damaged at other circuits we have to deal with, which would have been a retrograde step and much more serious than just one more race at the ‘Ring. When it comes right down to it, you either don’t go, or you get on with the job of racing.”

The drivers put their doubts behind them and took to the track on a sunny Friday. Lauda showed his ability to cut out emotions by proving fastest in the morning’s first qualifying session, recording a best of 7m10.3s, albeit some way down on his pole of the previous year, as times were compromised by a headwind on the long back straight that made gearing difficult. Local hero Hans Stuck was second in his March, and Hunt third.

It was a solid start, and that day James also took the opportunity to address a nausea problem he’d been facing, especially in races where he was leading comfortably and his concentration sometimes wandered.

“We thought that if we could wet my mouth during the race it might cure the problem, so we experimented with a bottle during practice for the German GP. The plan was that I would take a drink on the straight, the only place I had time, and then blow back down to the bottle until I could feel it bubbling and the line was clear.

“At the Nürburgring you’re doing 180mph on the straight and then the track goes wiggle-wiggle-wiggle-BRAKE, and you are as busy as you ever are in a racing car. Right in the middle of the busiest bit half a pint of orange juice came straight in my face. The whole bloody lot! Up the tube and all over the place.”

With rain forecast for Saturday, the second qualifying session on Friday afternoon session took on extra significance, as it looked likely to determine the grid. Hunt set out on a qualifying lap that saw him on the limit - jumping at the Flugplatz, passing through legendary spots such as the Fuchsrohe, Bergwerk, the Karussel, Hohe-Acht, Planzgarten, and finally onto the long back straight.

“I’m frightened, I don’t mind telling you,” he said after the session. “I’m glad to see the finish line every lap...”

He had logged a best time of 7m06.5s, while Lauda could not better 7m07.4s at a track where he was regarded as a specialist, despite his obvious dislike of the place. The third-fastest driver, Tyrrell’s Patrick Depailler, was over a second away from the Austrian, setting a 7m08.8s best.

On Saturday the expected rain came, and the sole qualifying session in the afternoon was washed out. Hunt didn’t even bother doing a flying lap to check the conditions. With his Friday time, he was on pole position for the German GP, having proved that he could tame the sport’s toughest venue. And he was 6.5s faster than team-mate Mass, a man who knew his home track as well as anyone.

Nevertheless, on a damp and foreboding race day Mass used his local knowledge to make what could have been a race-winning call.

“Before the start Herbert Linge, who was the chief of the ONS-Staffel marshals, told me the track was drying out,” the German recalls. “He had just come back from a lap in a course car, and I asked him how wet it was. Everybody had the same information, but I just decided to put on slicks. And the guys called me crazy.

“It was a difficult on a few stretches where there was water running still, and I aquaplaned a little bit, but then it settled, no problem. Everyone else had to pit, but then Niki crashed and the race was stopped…”

Lauda was rescued from his burning car, and Hunt was one of many drivers who stopped at the scene on the next lap around, and subsequently had to return to the pits and get ready for the restart. No one knew the extent of Niki’s injuries at that point, but nevertheless it was far from easy to set off again. With everyone now on the same slick tyres, Mass had lost his advantage.

“After the restart, I finished third,” said the German. “When I look at the pictures of me standing there at the end, I had a long face. I had a long face mainly because of Niki’s accident, and I was worried about him, but the other thing is I would have won it, and it would have been nice, finally a German winning the German GP at the Nürburgring after the war, and the last race there on top of it. It was really a great shame.”

Instead, the victory went to Hunt after a dominant performance at the front of the field, one that required his full concentration. He joined a stellar list of fellow Brits who had tamed the Nürburgring and won the German GP, including Tony Brooks (1958), Stirling Moss (1961), Graham Hill (1962), John Surtees (1963-64) and Jackie Stewart (1968-71-73).

No one knew for sure at the time, but it was to be the final F1 race at the old Nürburgring, Lauda’s accident proving to be the final straw. It meant Hunt claimed a place in the record books as the last man to win a German GP there.

The 1976 season meanwhile had plenty of twists and turns to come, culminating in Hunt’s title success at Fuji. Along the way he continued to show his mastery in qualifying, adding poles in Austria, Canada and the USA to his tally. However arguably no single lap was more impressive than the one that earned pole at the Nürburgring – and went a long way to silencing the critics.