Formula 1

Home of the McLAREN Formula 1 Team

Step into a world of exhilaration with McLaren Formula 1.

After our first taste of victory in F1 at the 1968 Belgian Grand Prix, McLaren has gone on to secure 197 Grand Prix wins, winning 12 Drivers' World Championships and nine Constructors' World Championships.

Whether it’s the F1 drivers on track, mechanics in the garage, the team on the pit wall, or engineers in the MTC, we are united by bravery, ingenuity, and the thrill of the chase.

Up next

2025 Schedule

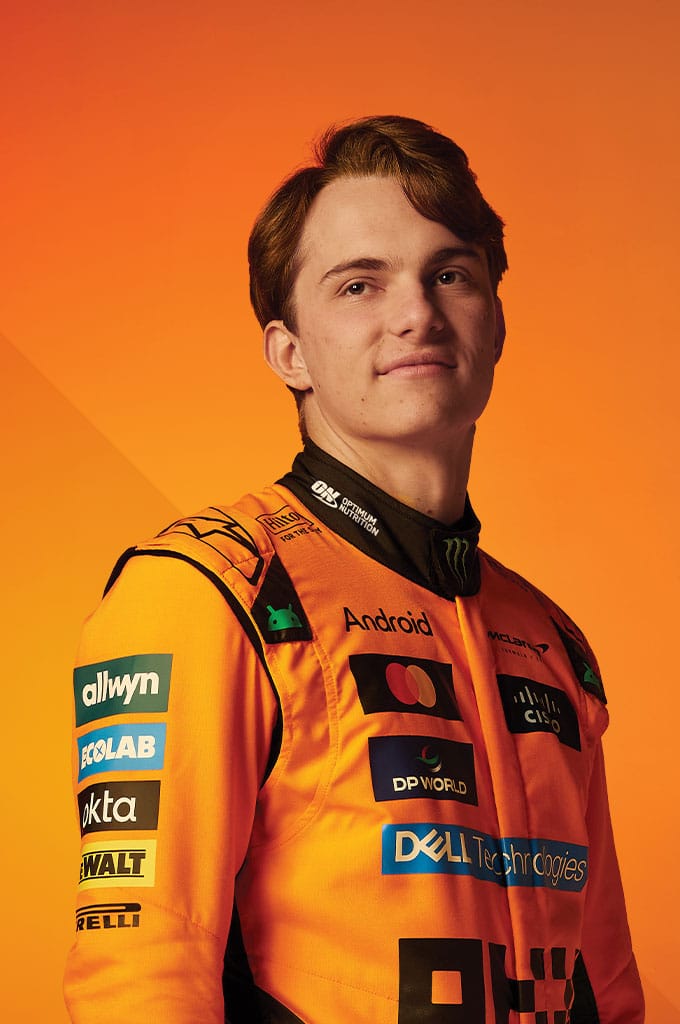

Our 2025 F1 Driver line-up

McLAREN Racing Live: London

Latest News McLAREN F1

Never Stop Racing