A tribute to John Hogan

1943 - 2021

You may never have heard of John Hogan, and there is no Wikipedia entry for him. You certainly wouldn’t have seen him swanning around the Formula 1 paddock seeking the full glare of the television lights.

Yet this quietly-spoken, unassuming Australian could probably claim to be one of the most important figures of the past 40 years in Formula 1. He was a trusted confidante of Bernie Ecclestone, the most powerful man in the sport for four decades, and negotiated Ferrari’s first sponsorship deal outside the motor industry - with the great Enzo, the founder, himself. He helped catapult James Hunt from party-going obscurity to world champion, and groomed a budding Ayrton Senna for fame, as well as effectively creating the modern McLaren team.

If it happened in Formula 1, then John Hogan knew about it, and the name of everyone who was someone was in the contacts book belonging to the man affectionately known in motor racing paddocks the world over simply as ‘Hogie’. He also managed one rare feat in a sport notorious for its sometimes bitter in-fighting: he was liked by everyone.

John Hogan, who died aged 76, in hospital near his home in Switzerland after contracting coronavirus, will be mourned for his gentle humour and compassion as much as for the business acumen that helped create the worldwide phenomenon that is Formula 1. When Hogie first entered the paddock as a young advertising executive, Formula 1 was little more than a festival for motor racing anoraks, held mainly on a few European racetracks, and was rarely on television screens; when he left the sport he loved, it was a global television event with grands prix from Brazil to Bahrain and Austria to Austin, Texas.

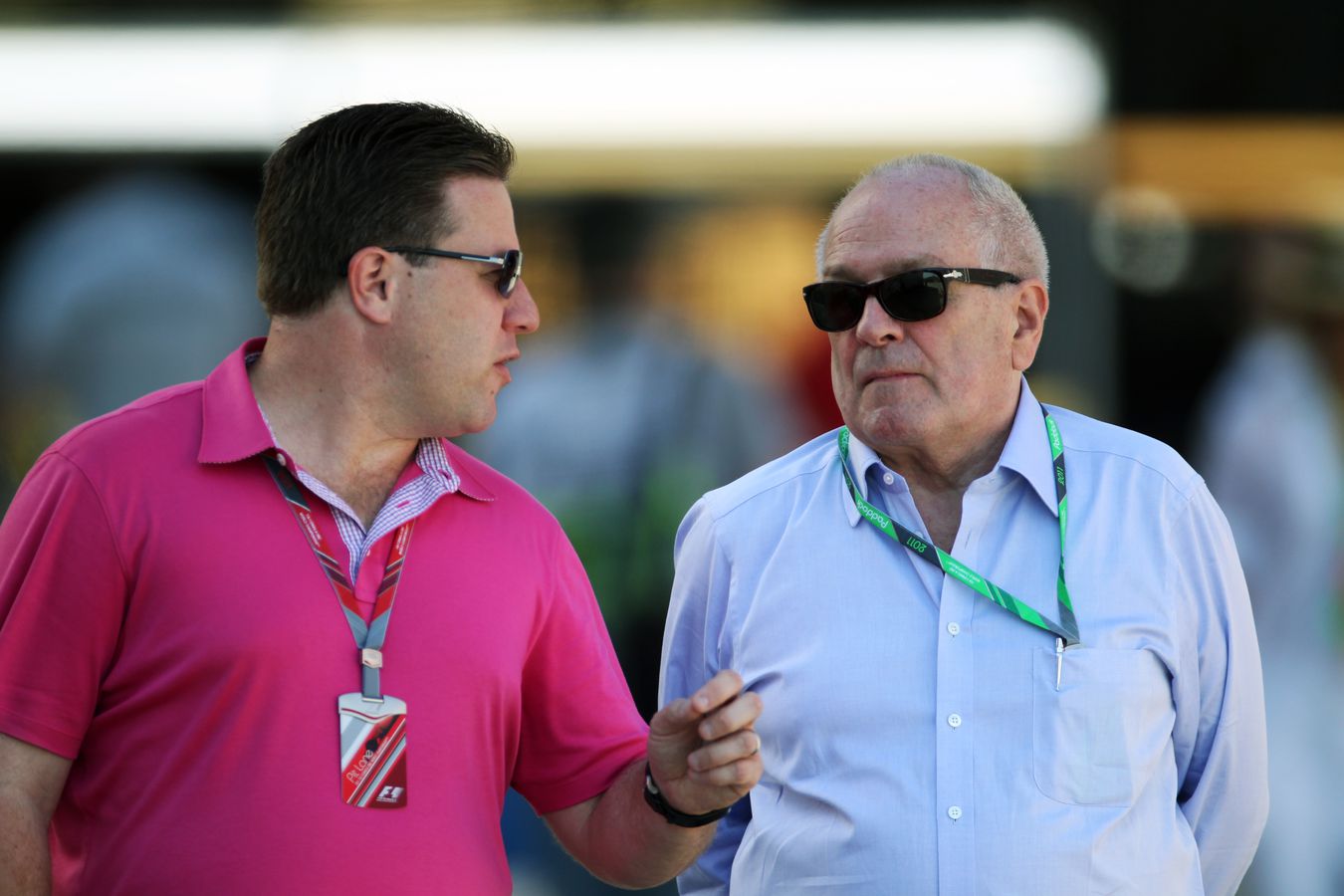

Zak Brown, McLaren’s chief executive, remembered with fondness the life and work of a man whose low profile belied his importance. “All of us here at McLaren are deeply saddened by the passing of John Hogan, who was not only a friend to the team, but part of its creation, helping it to become the famous name that we know today,” he said. “Without him, it is doubtful that there would have been all of the wonderful decades of success the team has enjoyed and with brilliant drivers, such as James Hunt and Ayrton Senna. He was also instrumental in creating the modern world of Formula 1 with pioneering sponsorships and ideas that are still effective today.

"On a personal level, though, John was a great friend and mentor. He taught me and many others in the business of Formula 1 so much and we are all grateful. He was a gentleman, a pioneer and a legend and will be much missed by me, McLaren and the Formula 1 community."

In a series of interviews early last year, John talked over his 40 years in Formula 1. Hogie’s pioneering work was crucial to the development of Formula 1 and many of its most famous names. Hogie was among the first to back Niki Lauda, and spot the rising talents of James Hunt and Ayrton Senna, and Hogie recognised the extraordinary managerial abilities of a mechanic turned junior team owner: he wrote the cheques for Ron Dennis, and Dennis wrote the modern history of McLaren, one of the most decorated of all sporting teams.

This exotic world of high-speed and sky-high spending was a long way from the thoughts of the son of a soldier as he grew up in his homeland of Australia, as well as Japan and Hong Kong as his father was posted around the Far East. It was in Singapore that Hogie discovered motor racing at the age of just 11. He found an old copy of Autocar and a feature about a young racing driver called Stirling Moss. He was captivated by the dashing exploits of this glamorous Englishman. “There were no mass communications as there are today, no television or newspapers in Singapore, so I read that magazine from cover to cover every day,” Hogan remembered.

Like so many children of service families, Hogie was sent to school in England where he made friends with Malcolm Taylor, a fellow motor racing enthusiast who later changed his name to Malcolm McDowell and starred in a landmark movie called A Clockwork Orange. They went to the old Aintree track to watch the 1957 British Grand Prix where Moss, already Hogan’s hero, won in a Vanwall – the first grand prix victory for a British-built car. “I remember it all so well,” Hogie said wistfully, delving into his memory bank for the sounds and smells of history. “Moss and the Vanwall and Jean Behra second in a Maserati.”

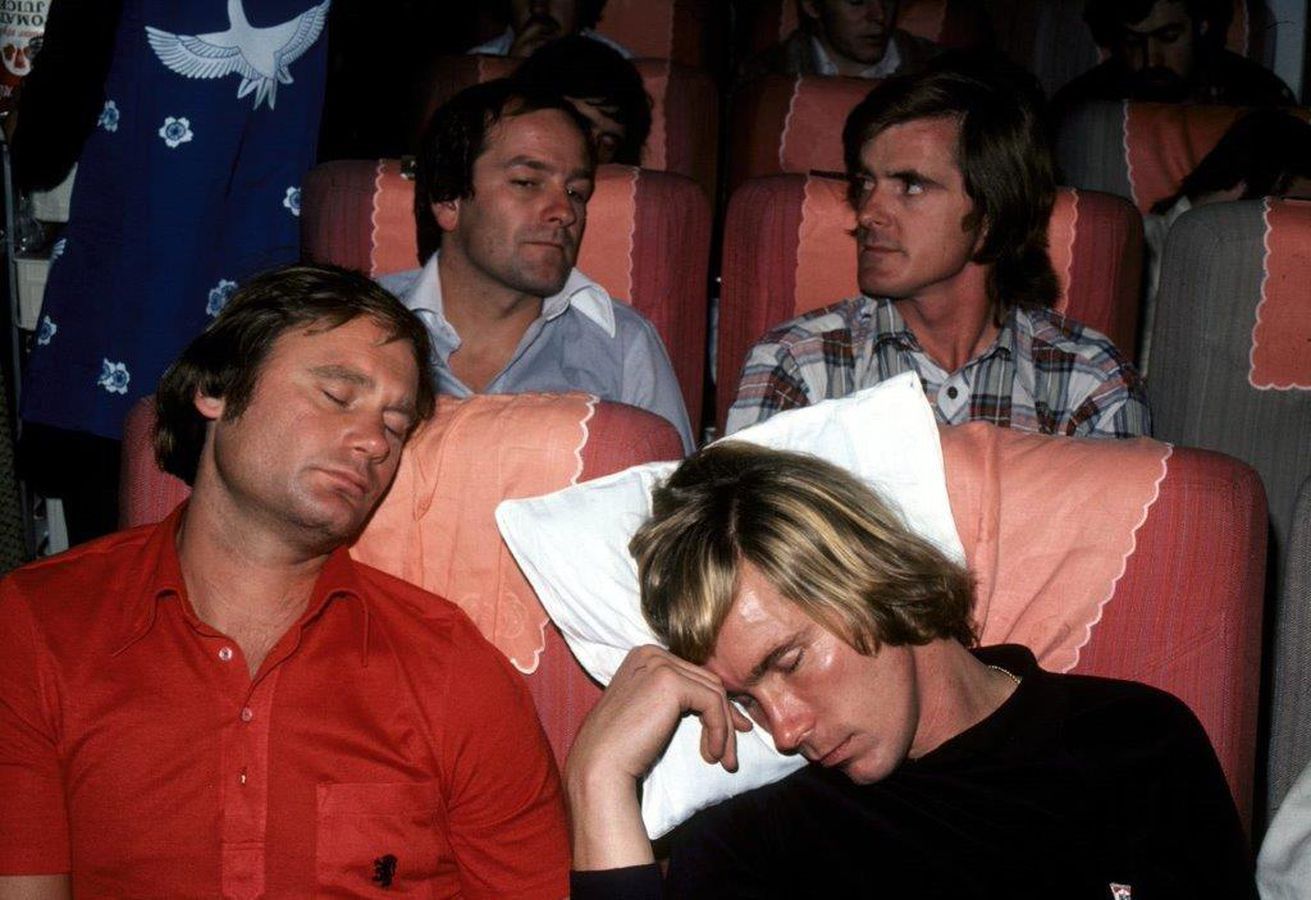

Hogie left school and Australia to join the world of advertising in London and was soon working on an account examining sponsorship deals for Coca-Cola. If the American drinks brand were unsure about entering Formula 1, this was Hogie’s free pass into the paddock where his legendary contacts book started to expand, so much so that he attracted the attention of a young and ambitious driver. “I was in my office one day when reception rang to say there was a young man to seen me,” Hogie recounted. The young man turned out to be James Hunt. “He had heard I was interested in sponsoring people and decided he would try his luck.” It was worth the journey, for Hogie put up £500-a-race for the young driver to work through the ranks and started an association that would end in a dramatic world championship victory.

Hogie was also working through the ranks when he joined Marlboro in 1973. The company already had a contract with the British BRM team, but Hogie could see the outfit was ailing. He went to McLaren in 1974 to sign the first sponsor deal with the team; McLaren won the first two grands prix of the season and Emerson Fittipaldi the world championship. Perhaps there was some sort of magic touch because Hogie was also investing in a truculent Austrian driver, whose mantra was: ‘No bullshit.’ Niki Lauda was world champion in 1975 and became a firm friend. “Niki just asked how much I was paying and that was it,” Hogie said, remembering the exploits of his old chum after Lauda’s death in 2019. “Absolutely straightforward and to the point.”

The now historic deal to take Hunt to glory was also straightforward – as soon as Hogie found his man. Fittipaldi has suddenly walked out of McLaren at the end of 1975 to join his brother’s Copersucar team. “We had no idea he was leaving,” Hogie said, “and now we were in a hole wondering who to get.” The name of Jacky Ickx, the Belgian who had won races with Ferrari and Brabham, was top of the list, but Hunt, who made his name with Hesketh, the renowned ‘Party Team’ financed by Lord Hesketh, moved into the frame for the 1976 seat.

Hunt had been offered a chance at Lotus, but was loathe to go to a team he considered a potential liability after the death of Jochen Rindt, a close friend and Formula 1’s only posthumous champion.

“It was a wet Saturday night and I was ringing every number I had for James,” according to Hogie. “It turned out he was at Lord Hesketh’s house in South Kensington with his girlfriend Jane Birbeck, so I went round to see him. He tried to play hard-to-get, but he had no options, apart from Lotus and he really didn’t want to go there because of his worries over safety after the death of Rindt. The deal was done in a couple of days and we got him pretty cheap.”

Hunt was not only the 1976 world champion, but the epic season – which saw Niki Lauda return from the brink of death after an horrific, fiery crash at the Nürburgring – turned into global box office viewing. Hogie was young and relatively inexperienced, but he could see Ecclestone weaving extraordinary deals with broadcasters from around the world, turning Formula 1 from a cottage industry into a television event, and he played his part in attempting to usher out the stuffy, formal world of a sport bound by tradition and dominated by Ferrari, the grandee team. Hogie invented the concept of grid girls and sent them out into towns near to racetracks to entice the public to watch motor racing for the first time. It was an innovation ahead of its time that was eventually copied the world over in sport. His diplomatic and business skills were also recognised by the sport’s governing body, the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), where he served for many years on the F1 Commission deciding on policy.

The grandest figure in F1 remained as remote as ever. Not to Hogie, though, who was one of the few ushered into the inner sanctum to meet Enzo Ferrari, the Godfather of Formula 1. Hogie had managed to get the Marlboro badge onto the overalls of Ferrari’s Didier Pironi for 1982, and a budding Canadian driver called Gilles Villeneuve. But he wanted more and went to meet Enzo at his Maranello headquarters. Enzo was resisting the infiltration into the sport by ‘outsiders’ like Marlboro and was contemptuous of the English teams – the ‘garagistes’ - queuing to do deals with this new generation of sponsors. “Don’t forget,” Enzo warned the young Marlboro man, “you are talking with the Pope, not the Archbishop of Canterbury.” But even the ‘Pope’ of Formula 1 could not resist the charming Australian, who brimmed with enthusiasm and talked of building the brand of Formula 1. Soon, the Marlboro name was on the rear wing of the Ferraris.

Perhaps Hogie’s most influential move, though, came as McLaren’s fortunes waned after the Hunt’s 1976 world championship. Hogie had worked with an ambitious Ron Dennis, who started out as mechanic to world champion Jack Brabham at Cooper, but was running his own successful outfit, Rondel Racing, in junior series. Hogie had brought sponsorship into Rondel, and could see there was huge potential in Dennis. “I knew he was different. Ron understood sponsorship, he understood how teams worked. He was brilliant with his technical people, but also had an instinct for what was coming in the future,” Hogie said. “He was all eyes, a very fast learner.”

In 1981, Hogie engineered a merger between the grand prix-winning McLaren and Rondel – like putting Boots the Chemist and a backstreet pharmacy together, according to Dennis. The facts speak for Hogie’s astute judgement and Marlboro’s investment as title sponsor: McLaren won 10 of its 12 world championships for drivers and seven of its eight constructors’ championships under Dennis.

The list of McLaren drivers is stunning too, from Lauda and Alain Prost to, arguably, the most charismatic of them all: Ayrton Senna. The Brazilian was brought to Hogie’s attention by a middleman before he entered Formula 1 and immediately recognised his potential, signing a $10,000 contract to put a Marlboro badge on his overalls and an option to sign for McLaren. Senna knew his worth and, after winning world championships in 1988 and 1990, he drove a bargain harder than his F1 cars when it came to negotiating a new contract. Hogie finally agreed to pay $1 million-a-race, which was fine until the San Marino Grand Prix, the fourth race of the new season. Teams arrived to set up, drivers arrived to go through their technical briefing …. but not Senna, the sport’s new superstar. The $1 million fee had not hit his bank account. Hogie recalled in an interview with Motorsport magazine in 2014: “I hadn’t allowed for how intransigent Senna could get. ‘When [the money] arrives, I’ll get on the plane,’ Senna told me. Senna had made his Varig flight land in Rio and wait there until the money arrived, then they could take off - with the other 360 passengers on board.”

Hogie was no gambler, but his instincts were sure. There was an earthquake in the Formula 1 paddock when he took Marlboro out of McLaren to full title sponsorship at Ferrari for the 1997 season. It was a coup for Luca di Montezemolo, the Ferrari president, but a leap of faith for Hogie, who believed that the newly-recruited Michael Schumacher and his technical team headed by Ross Brawn could succeed. It took until 2000, but then Schumacher ran away with five world championships to add to the two he earned at Benetton.

As Schumacher dominated F1, Hogie walked away from his job as Marlboro’s vice-president of marketing for Europe and straight into a new challenge when the Ford Motor Company asked him to run their Jaguar Racing outfit. The team had been set up in 2000 after Ford acquired Sir Jackie Stewart’s Stewart Racing, but it was an unhappy and unsuccessful ship when Hogie entered the Milton Keynes factory to start the 2003 season. Niki Lauda had been fired as team principal and 70 staff made redundant, while lead driver Eddie Irvine had been offloaded. Hogie, as clear-thinking and smart as ever, reorganised and recruited Mark Webber to be lead driver. Results improved immediately, although Hogie simply wanted to shepherd the team through the tough times to new management, although knowing at heart that Jaguar and F1 simply didn’t fit. “Jaguar’s racing history is Le Mans, not F1. The team management were being pulled all over the place because Ford in America wanted control. It couldn’t work,” he said.

Ironically, Ford decided to pull the plug a year later, just as it seemed Jaguar Racing had turned a corner, and sold to Red Bull for a nominal pound. John Hogan would go back to his contacts book, but now to become a wise man of the paddock, dispensing advice as a consultant and eventually joining Zak Brown at CSM Sport & Entertainment, one of the world’s biggest sports marketing groups, and engineering deals, just as he had going back to his first coup four decades earlier when he convinced Enzo Ferrari to take his word that he could sell Formula 1 around the world.

Hogie remained a familiar figure, sitting quietly in the corner of the McLaren or Ferrari headquarters motorhomes at grands prix, meeting and greeting a host of businessmen and women, giving a few tips to teams based on his long experience and saying hello to the host of friends he had gathered over four decades in Formula 1.

John Hogan leaves a legacy of, arguably, the most successful sponsorships in sport. More than that, he leaves a legion of admirers and friends who were privileged to know Formula 1’s own ‘Marlboro Man’.

John Hogan, born in Sydney on 5 May 1943, died on 3 January 2021, leaving behind his wife, Annie, and their son and daughter.