MCL34: the work starts here

Uncovering the first steps behind the build of our 2019 car

Four of our MCL33s are completing their 2018 tour of duty thousands of miles away from their birthplace at the McLaren Technology Centre.

But, in their absence, our designers, engineers and manufacturing personnel are beginning work on its successor, 2019’s MCL34, which has already been the subject of many thousands of hours’ development ahead of its debut early next year.

The first step in the construction of any new car is the manufacture of the monocoque, the carbon-fibre survival cell which houses the driver, fuel tank and energy recovery battery.

This super-complex and costly component – we only build four per season – is the biggest job of the year for our composites department.

Before embarking on such a huge project (due to the sheer size of the job, the monocoque is the first component of the 2019 programme that goes into build), the project delivery team hold an in-depth review meeting to ensure that they are equipped for the task ahead.

Gerry Higgins, McLaren’s Head of Manufacturing, explains: “About a month before we start production of the first monocoque, we’ll receive the first detailed designs from the drawing office, and hold a project launch meeting. In that meeting, we review the previous year’s programme, we discuss what we learned, what didn’t work as well as we’d have liked; what we should avoid, and how we can improve.”

Building a monocoque isn’t simply a job of painstakingly applying layers of carbon-fibre to a mould (although that does take up the majority of the work), but also about understanding how to optimise the tooling, the lamination process, the machining required once the chassis has been cured, and the detailed bonding required to glue the parts together.

The first patterns

The first step in the process is the creation of the pattern-work. This is a full-size replica of the external shape and dimensions of the monocoque, from which a mould will be created.

The pattern machinists spend two weeks faithfully creating the shape of the car from tooling block, a brightly coloured, durable polyurethane resin, from which laminating carbon mould tools are produced. This is a critical process, as the pattern-work will form the basis for all the tubs created, so a considerable amount of time and effort goes into the machining, assembly and finishing of it.

Making the mould

The pattern-work forms the basis for the carbon-fibre mould, essentially creating a ‘negative image’ of the chassis, into which the final carbon-fibre layers can be applied to form the monocoque. The mould is created from a tooling-grade carbon-fibre.

Think of the mould as looking a little like a bathtub, into which we’ll lay carbon-fibre to build the actual car. Making each mould takes about a week and a half.

The final step: the monocoque

Once the mould has been finished, the majority of the work takes place as the laminators start to build the monocoque itself. As the tubs need to be incredibly strong and totally precise, the engineers use laser alignment to accurately position each piece of carbon-fibre. The lasers beam an outline into the mould, showing the laminators the exact alignment of the next lay-up.

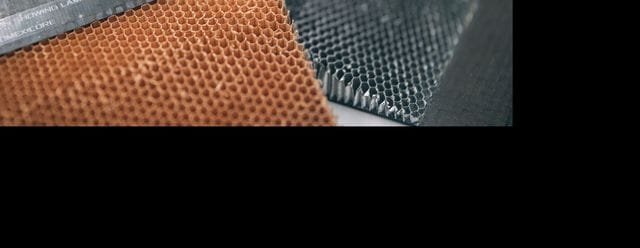

The tub is constructed in two parts – an upper and a lower – and it’s incredibly complex. All told, there’s some 600 separate laminating operations, 30 vacuum debulking operations and 10 full autoclave cure cycles – all constructed using six different carbon-fibre materials, eight different honeycomb core materials and three different adhesives.

A job that would take one person six months to finish, is completed in six weeks with a dedicated teams of laminators working on a 24/7 basis – that’s to say, the department is manned full-time seven days a week, only scaling back to a slightly reduced crew during weekend evenings.

Once the two halves are completed, they are then spliced together with an additional laminate band that bonds each overlapping layer together.

The finishing touches

Once the tub is laminated, it goes to the composites assembly shop where more detailing is added. The naked tub still needs to be machined to enable components to be bolted or bonded to it: these include the standardised deformable crash structures on each side, the sidepod ancillaries, and a number of externally bonded parts.

Once complete, the chassis is delivered to the paint shop for spraying, before finally arriving at the car-build area of the factory, where the power unit, suspension, hydraulics and electronics systems will be added to turn it into a fully functioning car.

Getting it right

Such a huge, complex job is fraught with difficulty. And, for Higgins and his team, getting it wrong is simply not an option – because it would cause huge practical and logistical knock-ons to an extremely tightly scheduled, critical part of the pre-season build programme.

“The level of complexity involved to build a monocoque generally increases from one year to the next,” says Higgins. “A lot of that comes from trying to take weight out and increase strength.

“We’re learning all the time. There’s a lot of interaction between the laminators and the designers during that initial build period as we learn how to make everything jibe smoothly together with the initial tub.

“Once we’re all safely through that initial phase with the first tub, we have the assurance and confidence to start on the second.”

And the third, and the fourth…