24 January 2017 18:00 (UTC)

Find out how F1 driver training has evolved since the 1950s

For much of its history, driver fitness in Formula 1 has been self-selecting: drivers with the correct physical attributes for the cars of the time could be successful; those who wouldn’t or couldn’t possess that sort of physique would fade from view.

The best drivers always adapt – but the trends over seven decades have seen tough, brawny drivers replaced by slighter figures and then, as the demands of driving in F1 dictate, the fashions have reversed.

In the last 30 years, F1 has demanded greater athleticism from its stars, gradually introducing better nutrition programmes, tailored training regimes to improve stamina and strength while reducing the effects of sitting in a cramped, unnatural position for hours on end. More recently bio-dynamics and bio-mechanical mapping have driven drivers to almost superhuman levels of fitness – which is why Jenson Button can run marathons in under three hours without it creating headlines.

It was not always so…

Look at images of Formula 1 drivers from the 1950s and the thing that stands out is how much more heavyset the drivers are compared to the spare physiques of their modern-day counterparts. They were beefy figures even for the times, with drivers like José Froilán González (aka the Pampas Bull) and Albert Ascari, nicknamed Ciccio, (‘fatty’) to the fore. Attitudes in F1, as in other professional sports, have placed an increasing premium on physical fitness as the decades have progressed – but the bulk of those original F1 drivers didn’t necessarily indicate an absence of preparation and an excess of calories.

F1 cars were heavy to drive in the 1950s: surviving footage of the day shows the drivers constantly wrestling their cars around circuits with a driving style quite different to the economy of movement in today’s cockpits. Drivers also had to contend with races often much longer than those of today. The 1951 French Grand Prix at Reims holds the record as F1’s longest (non-Indy 500) distance race with Juan Manuel Fangio winning the 77-lap 600km marathon in three hours and 22 minutes.

It was an era that demanded drivers with huge strength and stamina.

Towards the end of F1’s first decade cars began to change and the physique of drivers changed with them. Lighter, more nimble, mid-engined cars, and then monocoque chassis meant the drivers of the 1960s didn’t have to manhandle their cars in quite the same way as their predecessors, and thus required less bulk. Taking weight out of the car also meant taking weight out of the driver – and while physical fitness was still largely a matter of personal inclination or natural disposition, the era did produce champions that were noticeably leaner, Bruce McLaren himself being a typical example of a svelte 1960s’ racer.

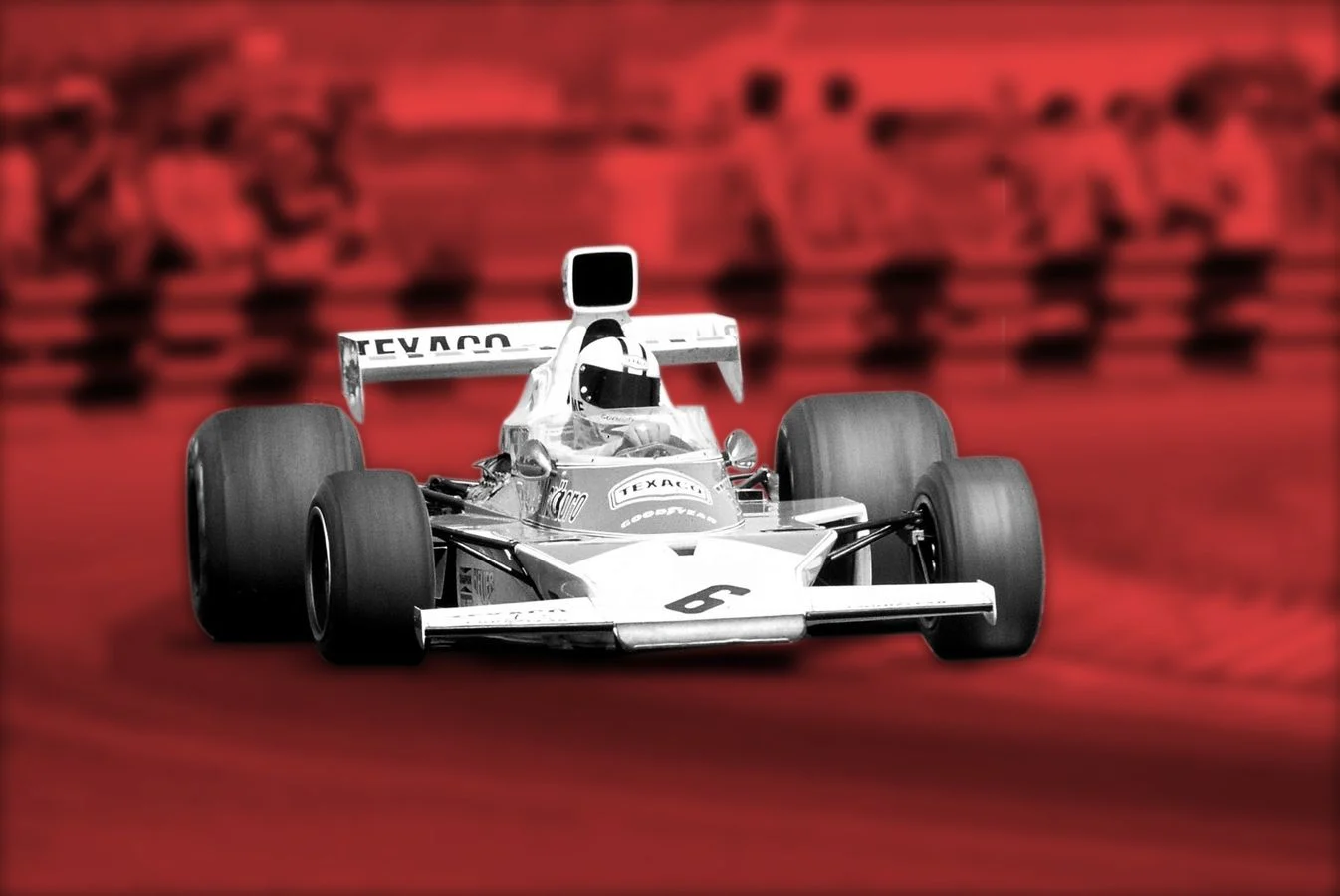

Wings appeared on F1 cars at the end of the 1960s, and cars started cornering faster and faster as downforce levels increased. In the 1970s, drivers began to add more upper-body strength to cope with increasing g-forces – in particular with the advent of ground-effect cars. Not coincidentally, the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s saw success for brawnier drivers such as Alan Jones and Keke Rosberg.

A less-obvious – but ultimately more significant – change happened in the mid-1970s when fitness expert, physical therapist and masseur Willi Dungl began his association with Niki Lauda. In 1976 Dungl, then known for his work in skiing, helped Lauda recuperate after his near-fatal Nürburgring crash. Dungl continued to work with his fellow Austrian after his rehabilitation, advising Lauda on diet and fitness. When Lauda came out of retirement in the 1980s to race for McLaren, Dungl’s influence and methods came with him, and became an integral part of a new holistic approach to driver fitness that would become a hallmark of the team.

The sheer brutality of driving a barely-controllable turbo car – particularly with 1200nhp available in qualifying trim – saw drivers again requiring almost as much muscle mass as had been the case in the 1950s.

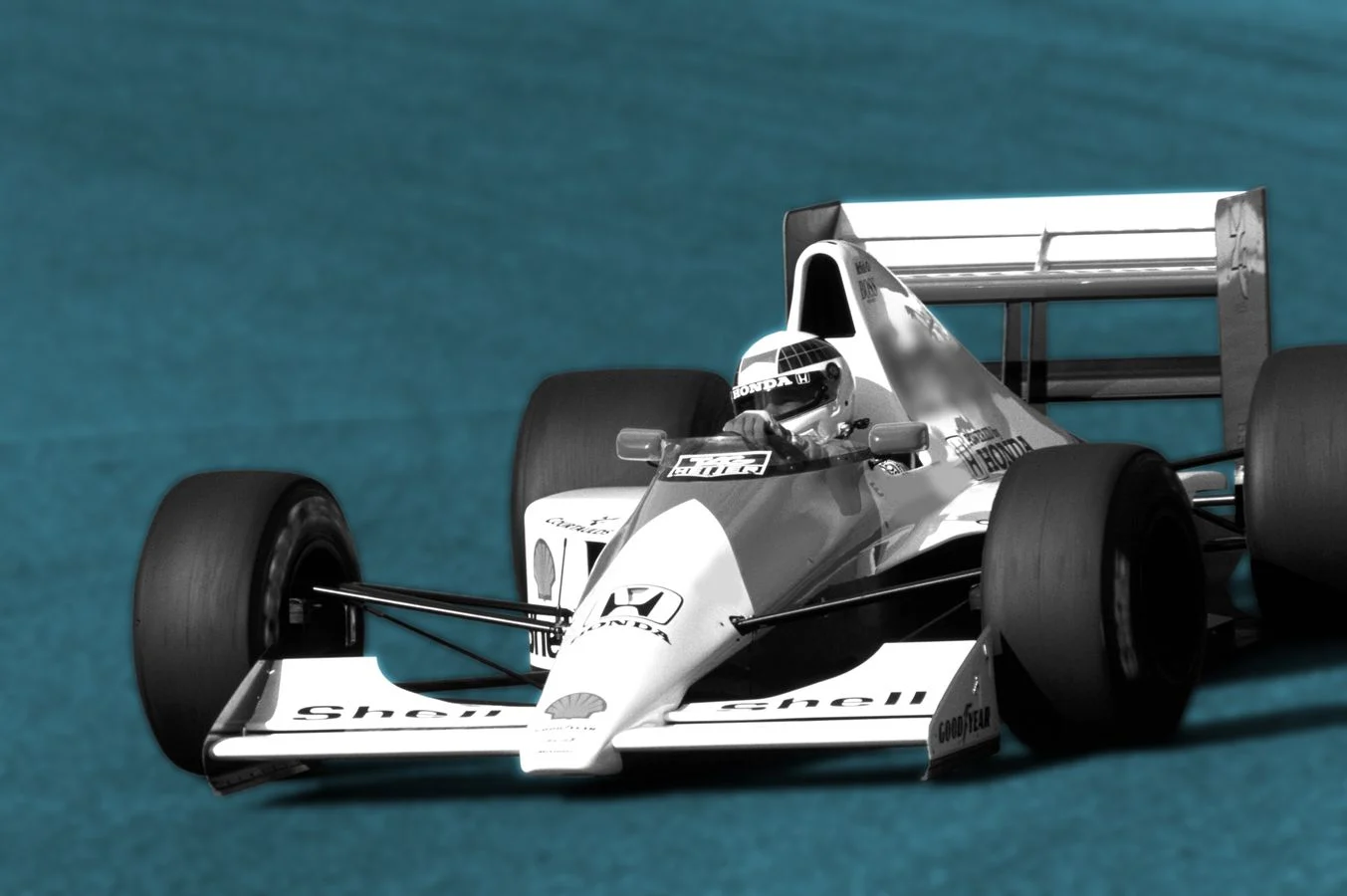

The end of the turbo era coincided with the first bloom of professional fitness regimes. At McLaren Alain Prost, and particularly Aryton Senna, were at the forefront of a wholesale shift in values as drivers became athletes. Josef Leberer, a fitness coach at the Dungl Clinic, was tasked with looking after the fitness requirements of the McLaren drivers.

“Alain Prost was already very fit when Senna arrived at McLaren, and while Senna was incredibly strong in his mind, he learnt quickly that to win you also needed to have the physical condition,” recalls Leberer. “He was finishing races exhausted – finishing because he had the talent, but he knew that if you wanted to be on top for years, you had to develop the fitness. So he got stronger and stronger. For him it wasn’t fun, but he knew he had to do it and so he did.”

Another driver to appear at McLaren during that era was a teenage Allan McNish. In the 1990s his was the first generation to properly embrace professional fitness as part of the motorsports package. “I started racing in 1987 and there are two things that are worth mentioning. The first is that drivers at this point didn’t have trainers. It wasn’t the James Hunt era of Saturday night parties, it was a clean-living environment without necessarily being the fitness-specific place it is today.

“The second thing is that, because we didn’t have experts in the field, we did the general fitness things, which usually involved running as fast as we could from A to B and lifting the heaviest weights we could manage. With hindsight, it was a totally inefficient way of training. It was only in the 1990s that the science began to really take hold.”

While Lauda had been a pioneer of sports nutrition, the concept took a further decade to really take hold and for diet to become just as big a factor in the training regime as cardio workouts. The Dungl Clinic staff not only trained McLaren’s drivers but fed them also, preparing meals to ensure the drivers got appropriate vitamins, and received a balanced intake of carbohydrates, fats and proteins to provide enough energy for racing – but not eating so much that they wasted energy on digestion.

Physical fitness came with a psychological bonus, giving drivers confidence in themselves but – this being Formula One – also providing a method of undermining the opposition.

“Senna always believed he was quicker than the rest and everyone else agreed with him – but he thought he was fitter too,” says McNish. “I remember seeing a photograph where he is doing press-ups beside a pool in Brazil, before the first race of the season. You saw his opposition lying beside the pool having a drink, while he was working, and I’m sure he was well aware of the psychological aspects of the sport.”

Michael Schumacher understood this better than most. The seven-time champion inherited Senna’s mantle and raised the bar for driver fitness in the 1990s. Schumacher ran, swam and, had a bespoke fitness regime that ultimately saw him supplied by TechnoGym with a mobile gymnasium that travelled around the world to races and tests for his exclusive use.

While the cars of the 1990s didn’t require the brute force and brawn of the turbo era, lap times were dropping rapidly as engine manufacturers dialled up the horsepower and teams found more and more downforce. The fitness regimes of the 1990s saw drivers concentrate on the muscles that take the biggest pummelling from cornering forces, namely neck, shoulder and core muscles.

Future McLaren driver Pedro de la Rosa made his F1 debut in 1998, by which point it was taken for granted that anyone getting into an F1 cockpit would be a honed athlete. “The worst thing for a racing driver is to feel the car is driving you, rather than you driving the car. F3 cars are easy, but when you step up to a higher formula like F3000, GP2 or F1 the exertion required to be quick is enormous. When I first drove an F3000 car I really had the feeling the car was driving me. It is a horrible sensation. That told me I had to train really hard, because I didn’t want to feel like that ever again.”

Speeds continued to rise in the 21st century with lap times (though not downforce levels) peaking in 2004-5 at the end of the V10 era. Strength and core muscles continued to be a factor, though stamina was also becoming a bigger factor as teams, away from grand prix weekends, ramped up the testing kilometres to unprecedented levels.

The statistics here tell their own tale. In terms of all-time accumulated testing mileage, the top 56 drivers on the list all participated in the first decade of the 21st Century. De la Rosa is ninth on that list, with a staggering 105,241km of testing to his name [Jenson Button is in P2 with 117,931km, behind only Luca Badoer. Fernando Alonso is 12th with 96,653km]. The Spaniard argues that the gap between fit and fittest may not have been apparent on a qualifying lap but it would tell towards the end of a 60-lap grand prix– and also on the test track.

“If you’re not fit you get tired, if you’re tired you make mistakes, it’s as simple as that,” he says. “It’s in the last 15-20 laps of a race when the fit guys get the advantage. You might not go slower if you’re tired, but when there isn’t as much oxygen going to your brain, bad things happen. You will make mistakes – maybe lose a place that should have been yours. That’s why, for me, training is the base. Everything else that makes you successful is built on top.”

One of the concepts bought into F1 by Dungl was an encouragement to cross-train in other sports, with a view to developing a holistic healthy body rather than simply the musculature required for racing. Swimming, for example, was seen as a good way to stretch a body used to sitting in the ‘clenched’ position of a racing driver, while mountain climbing was viewed as excellent preparation for F1, being goal-oriented and requiring a good mix of strength, stamina and concentration.

Dr Aki Hintsa, a world-class orthopaedic surgeon, and former chief physician of the Finnish Olympic Committee, developed a testing regime and supervised the fitness programmes of the McLaren drivers from the late 1990s until his untimely death last year.

“The driving posture in F1 is awkward and in the long run it causes anatomical and pathological changes to the body,” explained Dr Hintsa. “Even with the youngest drivers, you see lower back imbalances – when one side is more powerful than the other. If we don’t understand where an imbalance is, then there is a tendency in training to favour the more powerful side – and naturally the imbalance gets worse.”

The solution employed by Dr Hintsa and his team involved tailoring a fitness programme to each McLaren driver based on regular bio-mechanical and bio-dynamic assessments.

Formula 1’s first foray into hybrid technology began in 2009 with the provision for a Kinetic Energy Recovery System (KERS) added into the technical regulations. This had an unusual – and perhaps unintended – impact on driver fitness. While the minimum weight limit remained at its pre-2009 605kg limit, KERS package added an extra 30kg to the car, meaning that drivers needed to lose weight to counteract the increase in car weight.

With an extra 10kg adding around three-tenths of a second to a lap around a regular track, teams embarked on programmes to take weight out of the cars – but the simplest way to save weight (as seen by engineers) was to have a lighter driver – thus the off-season of 2008/2009 saw drivers radically alter their training regimes.

At its most extreme, the dieting requirements led to problems with dehydration and fatigue, particularly at races in tropical climates. At a more mundane level the difficulty for drivers was maintaining a high level of fitness without adding bulk. “I love fitness training but there are things I can’t do because I have to be a fixed weight,” said Jenson Button in 2013. “I can’t eat carbohydrates; I can’t build muscle.”

Paddock consensus in 2016 expected the wider tyres and projected increases in cornering speeds for 2017 to make the cars more physically demanding than ever to drive. Drivers are adapting their training regimes to compensate for this, in effect reversing the programmes of 2009 by adding muscle to cope with the extra demands. It’s a tough thing to ask of an athlete – but it’s nothing they and their predecessors have not done many times before.

As ever, in Formula 1, the optimal solution will be found.