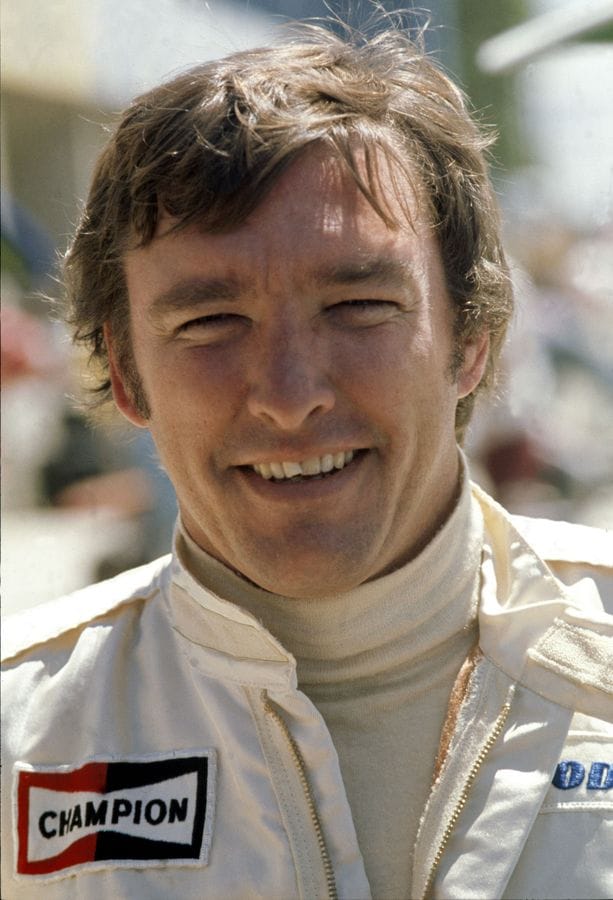

Johnny Rutherford wins Indy 500: 40 years ago today

‘Lone Star JR’ versus AJ at IMS: Texans – one by nurture, the other by nature – they drilled it at the 1974 ‘Energy Crisis’ 500.

Three-time winner Foyt, taking his record 17th start in the world’s richest race, was gunning to be the first to four.

Rutherford had never finished higher than ninth in his 11.

In fact, he’d not led a lap at Indianapolis Motor Speedway since 1963 – the year he won at Daytona on his NASCAR debut, in a prime-seat Chevy prepped by ‘Smokey’ Yunick at the ‘Best Damn Garage in Town’.

Yep, the racing career of this Kansas-born son of a US Army mechanic might have been different had not Indianapolis always been the draw for him. Its bricks were the gold at the end of the sometimes dusty, sometimes muddy, always dangerous Sprint Car road.

Mile after frantic mile of opposite lock – digging the groove or riding the cushion – those dirt ovals were neither chilled nor comfortable. Drivers couldn’t relax for a second.

And John Sherman Rutherford III – brave, smart and with a good heart – was superb at it. He beat Foyt, Bobby Unser, Mario Andretti and Don Branson to the 1965 national title.

He was lucky, too – lucky to be alive after a whaling endo at Eldora, Ohio, in April 1966. Stunned by a rock “right between the lamps”, he “hooked a rut” and “sailed out of the park”.

The accident broke both arms and fractured his career.

Having been selected to replace retiring two-times Indy 500-winner Rodger Ward, Rutherford had won on only his second outing for legendary car-builder and crew chief AJ Watson.

He did so in a new ‘funny car’, i.e. inspired by Lotus to place the engine behind the driver, on the speedway pave of Atlanta in August 1965.

Adaptable, JR was a hot ticket.

Sadly, injuries would soon render him less flexible and less in demand. He wouldn’t win again in the premier Champ Car series for eight years.

It was Indy 1970 that put him back on its map.

Having missed pole position by fractions, he ran second, ahead of Foyt, until the clutch of his four-year-old, much-modded Eagle-Offenhauser turbo jammed at the first pit stop. It eventually retired because of a cracked exhaust header after 135 laps.

This performance was regarded as a surprise. Rutherford – supposedly damaged goods, remember – was reckoned to be capable but not outstanding by some observers.

Yet McLaren’s perspicacious boss Teddy Mayer signed him over breakfast at the end of 1972.

“Most of the teams I had driven for before then were the preserve of sportsman car-owners,” says Rutherford. “They were guys who had other business interests; racing was their hobby and they hired a crew and a driver to run their car.

“Well, racing was Team McLaren’s business. They quickly began to figure it out and get organised to become a winning proposition.”

McLaren arrived at Indy in 1970 with a single-seat reworking of its dominant Can-Am chassis. Its performance was solid.

Its 1971 return with a tailor-made car was spectacular.

Designer Gordon Coppuck, still feeling his way in the role and thus content to leave the team’s Formula 1 challenger to the more experienced Ralph Bellamy, rendered the Indycar establishment obsolete with his winged M16 ‘wedge’.

Peter Revson put his works car on pole – an 8mph increase over the previous mark – and finished second. Yet his had been no match for the Penske-run privateer version of Mark Donohue, which was romping away when its transmission failed moments after setting fastest lap.

Speeds at Indy leapt again in 1972: from 179mph to 196 for pole.

Unrestrained turbos had given the robust Offenhauser four-cylinder, designed in 1931, a new lease of life. And increased downforce – wings no longer had to pretend to be a piece of bodywork – harnessed its raging horsepower.

It was, however, a more restrained approach that allowed Donohue to take victory in Penske’s M16B.

Initially Team McLaren restricted itself to the major 500-mile races on superspeedways: Indy, Pocono in Pennsylvania and California’s Ontario. But the stemming of its Can-Am cash flow by the arrival of Porsche caused it a rethink.

That’s where Rutherford came in: a full Indycar programme with an experienced oval racer.

McLaren in turn gave him what he had long craved: consistency and competitiveness: “They were very methodical. Everybody had a job and everybody did it. They brought something, for sure: their thoroughness, their work ethic.

“The first time I tested the car, however, it was no different from any other that I had driven at Indy: we couldn’t get it to stop understeering.

“We ran it without any great acclaim at the races prior to Indy, too – but suddenly it was a completely different car. I think maybe they changed the roll-centre to get its front end to stick. Now it suited my style and we set a new standard.”

Rutherford and M16C – more rounded cockpit surround, reshaped hip radiators and extended engine cowling – clocked the first 200mph laps of Indy. Unofficially.

Officially, they missed out by two-tenths – but still grabbed pole at 198.413mph.

“The M16 was the first time I had been flat-footed for an entire lap. With 1000bhp, they were exciting times,” understates Rutherford.

“The Offenhauser was a racing engine of note. It shook like crazy in its atmo form. We used to tape hardwood splints to the back of the steering wheel’s spokes to deaden the vibration. That cured it some, but, if ever you got a chance to let go of the wheel and wiggle your fingers, you did it.

“That was less of a problem in its turbo form, when the engine was behind you and you were surrounded by a monocoque chassis.

“It had pretty good torque but, even so, you had to keep it up on the cam because it wasn’t explosive off the corners like a V8. You had to stay on top of it, not let it die.

“The fastest lap of Indy for an Offy-engined car is a record that I am very proud of.”

Yet still the win wouldn’t come. A loss of boost pressure caused by another cracked exhaust header saw Rutherford slip to a distant ninth.

That race’s early finish – after 133 laps because of rain – came as blessed relief from a much-delayed and ill-fated 500.

Salt Walther’s start-line accident had not only put him in hospital – the front of his inverted McLaren sheared off – but also it sprayed burning fuel over spectators.

When at last the race restarted – on its third day! – Swede Savage suffered an almighty accident that scattered his Eagle to the winds and caused an understandably panicked crew-member to step into the path of a rushing ambulance.

These deaths – Savage succumbed after a month in hospital – compounded that of Art Pollard, killed by a fiery accident during a morning practice session.

“Art’s was a terrible situation,” says Rutherford. “He was a dear friend of mine. He and his wife, plus my wife Betty and I, and a few others, had been to New Orleans on a getaway before returning to Indy.

“It was hard to take. But it was on the same day that I set that record. That was racing then. Stuff like that happened every now and again to wake us up.”

Governing body USAC’s response was to drastically shrink rear wings and introduce a pop-off valve to limit boost. Also, fuel tank capacity was reduced from 75 US gallons to 40, none of which could be carried in the right-hand sidepod.

“Our 1973 car, which had a wing the size of a picnic table, had a funny characteristic: it would wind up like a spring and then uncoil and cause me to spin,” says Rutherford. “The 1974 car [M16C/D, with its F1-style cockpit and curved aerofoil-section wing atop a single monocoque pillar] had a better balance.”

A second consecutive Indy pole looked to be on the cards – until Rutherford’s qualifying engine let go during Pole Day’s warm-up.

“The guys set a new track record for changing an engine – 58 minutes – but when we went to our place in the line [decided by ballot], an official said, ‘No, you weren’t here when the line was formed.’ We pleaded our case to the chief steward, but he wouldn’t relent.”

Unable to qualify in that first session, Rutherford would have to start from the inside of Row Nine – despite setting the second-fastest qualifying speed.

Only three men had won from lower than 25th on the grid – and all those were pre-WWII: Ray Harroun (1911), Fred Frame (1932) and Lou Meyer (1936).

Though Rutherford’s rapid rise through the field was aided by a slew of early retirements for men ahead of him – six in as many laps – it was very impressive nevertheless: “I passed the others whenever I came to them. No matter where they placed themselves on the track, I went by. It’s very seldom like that in motor racing.

“I was up to third within 12 laps. I knew then that if we had no problems, and if we made good pit stops, that we could win.”

A limit of 280 gallons of methanol for the race – a very 1970s America 1.8mpg ‘efficiency’ – and the smaller fuel tanks had placed a greater emphasis on strategy. With at least seven stops scheduled, pit crews would be more important than ever.

Rutherford was second behind the Coyote of pole-sitter Foyt by the time of the first stops, whereupon McLaren put down a marker with a sub-20-second turnaround.

Meanwhile Foyt, setting a record pace, was already fitting new rubber.

“AJ had a little more engine than us, with that Foyt-Ford V8,” says Rutherford. “I’d just be trying to pass him on the straightaway when I’d have to lift off and give him back the racetrack. If I could’ve got past him I knew that I’d be gone because I was so much faster in the corners.”

Miscommunication during a Foyt stop allowed Rutherford to finally move into the lead of an Indy 500. And there he stayed through laps 65 to 125.

His rival, though, was not done.

Foyt twice regained the lead – once at a restart and once by clever blocking use of a backmarker – but each time Rutherford stayed calm in AJ’s slipstream: “I didn’t want to force the issue. I knew that if I could keep the pressure on that he might run out of right-rear tyres or engine.”

A puff of oil smoke on lap 140 indicated that it would be the latter. Foyt was black-flagged for dropping oil – his scavenge pump’s main-shaft had broken – and he swung into Gasoline Alley to retire.

McLaren methodically reeled off its remaining pit stops – jacked up its tank and jiggled its hose to ensure every last drop was drained – and Rutherford responded to its ‘EZ’ signal.

But experienced Jim McElreath, another Texan, hadn’t read the script.

“He was notorious for getting in the way,” says Rutherford. “He believed that this was his part of the track and that you had to get by him the best way you could.

“I had been having trouble with him for a couple of laps, and so I dove by him and pulled alongside Pancho [Carter, Rookie of the Year]. I think that must have startled Pancho, because he twitched to the right, got into the ‘grey’ and spun.”

Rutherford apologised for the incident as he stood in Victory Lane – and also dedicated the win to his ill father. A popular winner, he had done much to help erase the dark memories of 1973 and restore Indy’s sheen.

He would win it twice more – a second victory for McLaren in 1976 (in M16E) and with Chaparral in 1980 – but 1974 stands out: “Because of the battle I had with Foyt and because of how good my car was.

“I’d always told Betty that if ever I found a team that wanted it as badly as I did, I’d be a winner.

“That I was with that team for seven years tells you something: McLaren fitted the bill perfectly.”