The Story of RUSH

It was often said of the dramatic 1976 Formula 1 season that the story of its up and downs read like a film script. It took nearly 40 years, but the battle for the World Championship between James Hunt and Niki Lauda was finally put on the big screen as Rush in 2013, courtesy of top Hollywood director Ron Howard.

The film had much to live up to, because of the fondness of racing fans for classics such as Grand Prix and Le Mans – not to mention the fact that this was a true story, and Hunt and Lauda were real characters that people knew and loved.

However the consensus on its release was that Howard and his team had got it just right, creating a film that did justice to the sport and its subjects, while at the same time providing great entertainment.

Howard was the public face of Rush, but the man who actually started the project was screenwriter Peter Morgan. The Briton is well known for taking real events and people and using them as the jumping-off point for scripts that delve into the human psyche. He received Oscar nominations for his two most celebrated works, The Queen and Frost/Nixon, the latter directed by Howard. It was back in 2010 when Morgan was first approached about a motor racing story.

“A producer from America rang my agent and asked if I would be interested in writing a story about F1 in the 1970s,” he recalled. “My initial instinct was not really, because I’m not an F1 fan.

“But I asked for a couple of days, I did a bit of research, and I found the Hunt/Lauda story. The elements of the story were very personal to me – because I’m married to an Austrian woman and she knew Niki, because we live in Vienna, and because it was a story about a rivalry between an Austrian and Englishman, it felt very quickly like it was going to the heart of things that were dear to me.

“I told my agent, ‘I’m so thrilled about the Hunt/Lauda story.’ Then I got the feedback, no, they wanted to do Jackie Stewart! I said, ‘I don’t want to do Jackie Stewart, I want to do this.’ I’m sure there’s a great film to be made about Jackie, but this had deep tentacles into areas of my own interest and passion.”

A meeting was arranged between Morgan and Lauda when both men were holidaying in Spain. Niki was soon convinced that the writer would do his story justice by focussing on the 1976 season – and giving equal screen time to Hunt.

Wearing his producer hat Morgan began to generate some finance, and the project that became known as Rush started to gather momentum. Action specialist Paul Greengrass, best known for his work on the Jason Bourne movies, agreed to direct.

Meanwhile on a trip to Los Angeles Morgan met his Frost/Nixon partner Howard. The American was not a motor racing fan, although he had attended the 2008 Monaco GP with his friend and mentor George Lucas.

“We caught up over a breakfast,” said Howard. “It was just, ‘What are you up to?’ At that point I was really focussed on trying to get Dark Tower made, a series of Stephen King books. He told me about this F1 story, and it was fantastic. He said he was developing it with Paul Greengrass, and I said, ‘I can’t imagine anybody better. What a great movie, I’m dying to see that.’

“And then I just thought I ought to put my careerist hat on for a moment. I said, ‘If Paul blinks, I’d love to read that script.’ It just sounded cool, and I wanted to see the movie. And that’s also a good indication that it’s something I’d enjoy working on.”

Some months later Greengrass found himself double booked, and he pulled out of Rush.

“Peter called me and said, ‘Paul is going to do Captain Phillips,’” Ron recalled. “It was a movie that had to work at a particular time due to weather, and Tom Hanks’ schedule.

“He said, ‘I’m showing Rush to a few directors, to be fair. But you raised your hand, were you serious about that, or were you just being polite?’ I said, ‘I’m very serious, Dark Tower is not coming together in a timely way, but I’d love to read Rush...’”

Howard quickly signed up: “It was undeniably great drama, with Niki’s comeback and the conflict between these characters. The way Peter was writing it was very entertaining. I felt like this is all too rare. So I jumped in. Probably over a period of less than 48 hours, I committed to it.”

Howard’s Imagine Entertainment production company came on board, along with Crosscreek Pictures – backer of Oscar-winning Black Swan – and Universal. However, Rush remained officially an independent British film, made by a largely Anglo-German crew, so the widespread perception that it would be a “Hollywood” take on F1 was a little unfair. Howard brought with him only his business partner and second unit director Todd Hallowell, and his editors Dan Hanley and Mike Hill.

The casting could make or break the project. Daniel Bruhl emerged as the top candidate for Lauda, and the German-Spanish actor had the benefit of being able to spend time with the real Niki, and work on his accent and mannerisms.

“Peter nominated Daniel early on, and he was right,” said Howard. “I met him and made the decision that hour. He had to prove himself to Niki, and then Niki liked him a lot, and saw that he was a good student and a good listener.”

Finding Hunt proved more difficult: “I had a nagging suspicion that we might not be able to make the movie if we couldn’t get a great James. He’s so iconic in the sport, and especially in the UK, and I was very worried about it.”

Australian Chris Hemsworth won the role by adopting a British accent and submitting a video he’d made of himself reading a Hunt monologue from the script. Howard and Morgan knew that they had their man – although the Thor star had to trim down his Marvel superhero physique, and work hard to hone his accent.

In August 2011 Howard shot some exploratory footage of historic F1 cars running at the Nurburgring. The visit answered some important questions about the balance between real action and CGI: “When we shot at Nurburgring and realised how much we could do in camera, it changed a lot, and a lot of our budget shifted out of digital, into practical.”

Meanwhile Morgan and Howard continued their research, meeting people like former McLaren team manager Alastair Caldwell, as well as paying a visit to the current McLaren base. They also had a tense dinner with Hunt’s family.

“They felt burned by a lot that had been written,” said Howard, “always feeling that it was mono-dimensional. I tried to say that’s not really the kind of work I’m interested in doing, and they just didn’t trust us.

“I can understand why, because everyone loves sex, drugs and rock and roll and wants to deal with it. We did too, we weren’t going to shy away from it, but we didn’t want it to take over our story. Peter never did, I never did.”

Months of planning followed as Howard and his crew booked circuits, scouted locations, and sourced the other stars of the film – the cars. Much of the footage that reached the screen involved genuine 1976 F1 chassis from the historic racing scene, including Hunt’s actual M23-8 championship winner.

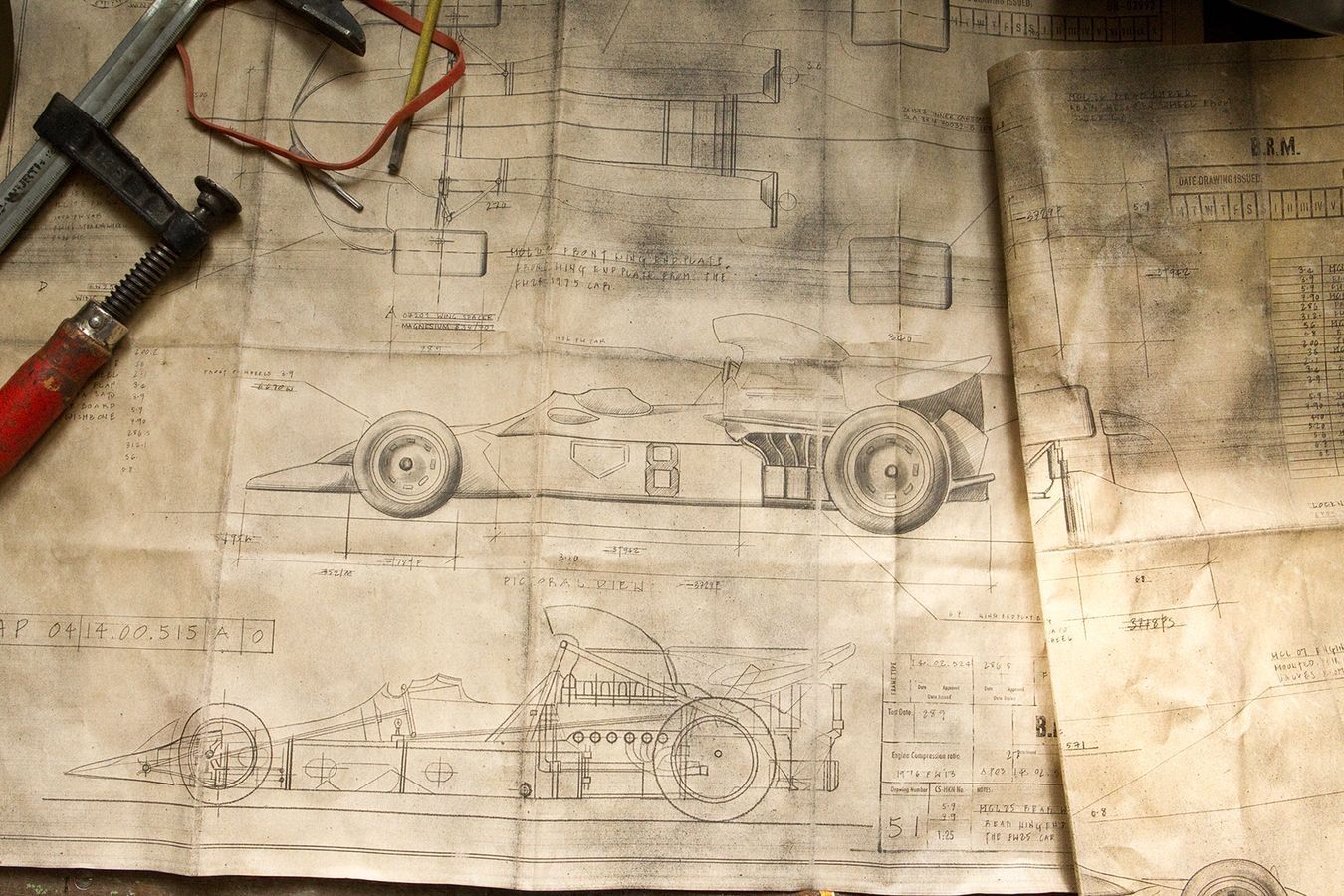

The Rush team also created replica cars for the trickier action scenes, and for use when local noise restrictions meant that it wasn’t possible to run a DFV or Ferrari flat-12. Two McLaren M23s and three Ferrari 312T/312T2s were built, while there was also the option to swap bodies to create rarer beasts such as the Ligier JS5 and Brabham BT45, since the originals weren’t available. Two BRM P160s that figure early in the story were also created.

Principal photography began on February 22 2012, and Howard followed a tight and meticulously planned schedule that ran through to May 22. Most of the locations were UK-based – a pit-lane complex built on a former airfield was the main home – supplemented by trips to Germany and Austria.

The racing action, filmed mostly at Donington, Snetterton, Cadwell Park and Brands Hatch, was carefully choreographed: “We started doing storyboards of all of the sequences to make sure that we didn’t overproduce them and overshoot,” Howard explained. “Because it would be a crime to invest too much in a race that we didn’t need. We simplified a lot of races that way, because we just realised that for our balance, we had too many races.

“We were trying to be as authoritative as we could afford to be, while knowing that occasionally we’d have to combine the elements of a couple of races into one. It was always keeping one eye on the story and what was ideal, and the other eye on the practicality of it, and what we could afford to do.”

On one day of action a record-breaking 35 cameras were in play, including those fixed to cars, capturing everything in sight. With so much footage in the can there followed months of editing, plus the complex mixing of the soundtrack at a Berlin studio, which meant getting all the engine sounds just right, and weaving in a score from celebrated composer Hans Zimmer. Howard finally signed off on the finished Rush in early 2013, and it was released that September.

The film was nominated for four BAFTAs – winning for editing – but curiously it was ignored by the Oscars, possibly because it emerged in a year packed with highly-acclaimed films based on subject matter more familiar to a US audience. But what really mattered to Howard was that racing insiders, including Lauda himself, were happy with the end product.

“It’s important to me to honour the sport and the people who build their lives around it, to try to get it right,” he said just before the release. “That sounds a bit idealistic, but I’d be embarrassed if we didn’t achieve that, more or less. But I also think Rush is very entertaining, and when people hear from others that it’s very authentic, it heightens the experience for them too. That validation from people who really do know is something that a movie like this really depends upon.

“To me, that’s really our one advantage over the greats, which were Grand Prix and Le Mans, in that those were fictional stories. Clearly those are the enduring movies, and the best examples. It’s a tricky sport to get right and to capture.”