Shy and retiring, sometimes stand-offish, but ultimately, incredibly quick.

We delved into the archives and found this hidden gem – a rare and very frank interview with the great Denny Hulme, great friend of Bruce McLaren, fellow Kiwi, and hugely talented Formula 1 (1967) and CanAm (1968) world champion.

Denny was also a key instigator of new safety initiatives in what was still considered an extremely dangerous sport. In 1973, shortly before this article was written, Denny and Bruce had pioneered the first Graviner life-support system on a Formula 1 car, which supplied breathable air to the driver in the event of a fire. Denny had also begun the role of president of the Grand Prix Drivers Association, a mantle which he took very seriously.

In this fascinating, honest and outspoken interview, Denny reveals the real man behind the steely, sometimes cold exterior, and his plans for revolutionising the crazy world of Formula 1.

This article was originally written by Tony Rudlin in the week ending November 24 1973 issue of Motor magazine, which sadly is now no longer in publication, and was absorbed by its rival Autocar in 1988).

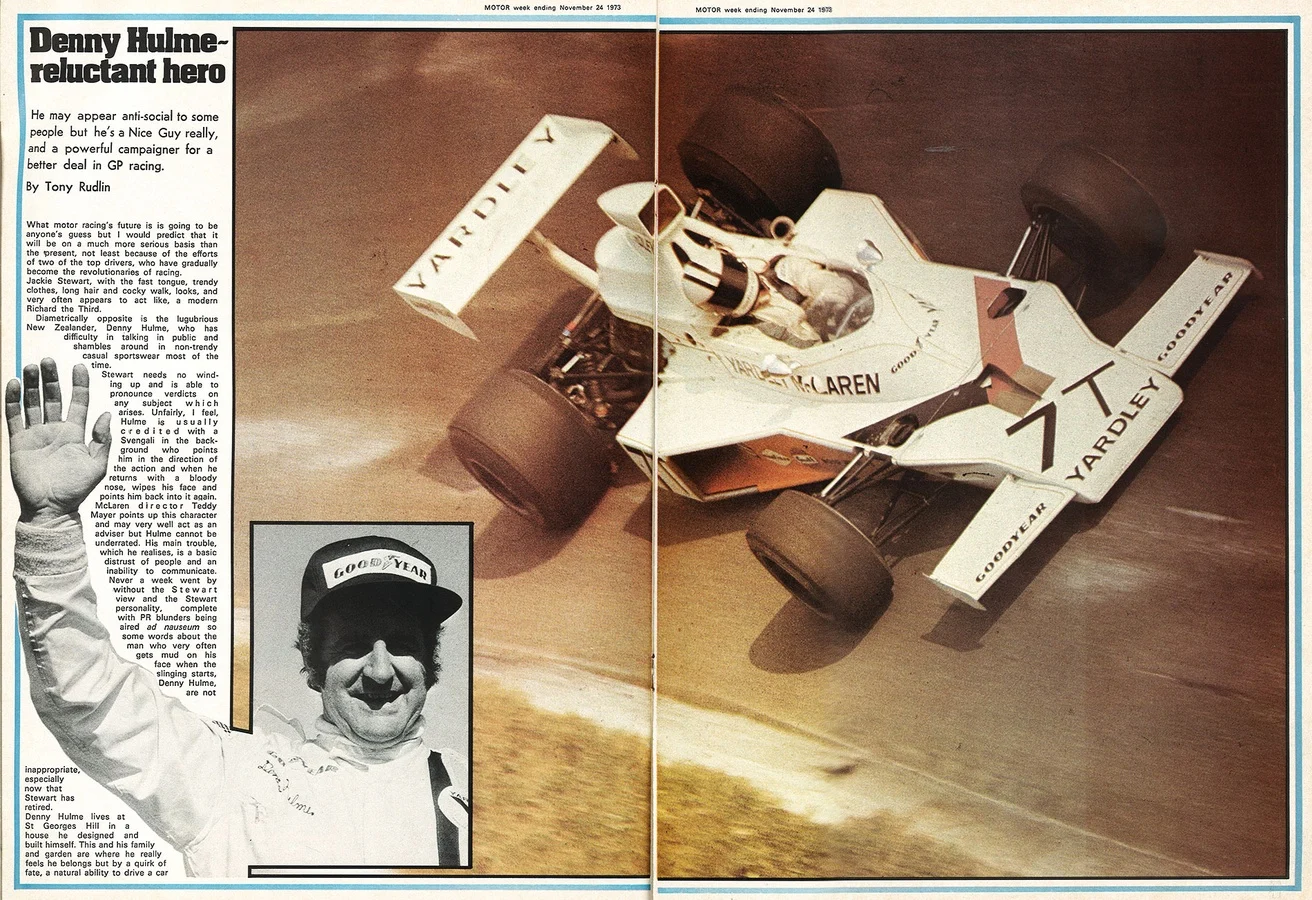

He may appear anti-social to some people but he’s a ‘Nice Guy’ really, and a powerful campaigner for a better deal in GP racing.

By Tony Rudlin, Motor, week ending November 24 1973.

What motor racing’s future is is going to be anyone’s guess but I would predict that it will be on a much more serious basis than the present, not least because of the efforts of two of the top drivers, who have gradually become the revolutionaries of racing.

Jackie Stewart, with the fast tongue, trendy clothes, long hair and cocky walk, looks, and very often appears to act like, a modern Richard the Third.

Diametrically opposite is the lugubrious New Zealander, Denny Hulme, who has difficulty in talking in public and shambles around in non-trendy casual sportswear most of the time.

Stewart needs no winding-up and is able to pronounce verdicts on any subject which arises. Unfairly, I feel, Hulme is usually credited with a Svengali in the background who points him in the direction of the action and when he returns with a bloody nose, wipes his face and points him back into it again. McLaren director Teddy Mayer points up this character and may very well act as an adviser by Hulme cannot be underrated. His main trouble, which he realises, is a basic distrust of people and an inability to communicate.

INLINE-MEDIA SMALL

Never a week went by without the Stewart view and the Stewart personality, complete with PR blunders being aired ad nauseum so some words about the man who very often gets mud on his face when the mudslinging starts, Denny Hulme, are not inappropriate, especially now that Stewart has retired.

Denny Hulme lives at St Georges Hill in a house he designed and built himself. This and his family and garden are where he really feels he belongs but by a quirk of fate, a natural ability to drive a car at high speed, he has to content with the problems of being a public figure.

“When I retire I will head for New Zealand. It’s where my parents are, it’s my home. It’s quiet there and I would like to get away from the hurly-burly of life in England. Although living in St Georges Hill is like living in the country.

“The plot was bought and the house built so I can get away from people. I have this terrible urge to get away from the hustle and bustle and be alone to do what I want to do. If I want to lay around and sunbathe – that’s what I want to do. I don’t think I am anti-social. It’s just that I can’t come with the everlasting call on my time. The telephone going, Press and people ringing me up and wanting to know this and that. It’s not in my make-up. I hate public intrusion into my private life. Funnily enough, I have built a house of glass and people can come and see in.” With glass houses and a job which attracts millions all over the world Denny might seem to be a case of a square peg in the proverbial round hole. He agrees.

“That’s why I may appear anti-social at race tracks. Except to certain people. Certain people can be around as much as they like and it doesn’t bother me. I just have a few friends I don’t mind being around.”

Although he has tried to control the way he feels about people he still finds himself unable to cope on many occasions. “The general screaming mob makes me just want to get away. Something inside of me just boils up and boils up 'til eventually someone’s just got to touch me on the shoulder and I explode, whomph, that’s it. Wilson Fittipaldi is the same way, though he’s got a shorter fuse than I have. Yet other people can tolerate all the gibberish in the world. Jackie can. [Peter] Revson can have fans climbing over him all day and he will sit there signing autographs – no problem. I can’t. I don’t get claustrophobia but it’s a feeling very like that. I could be locked away in a small chamber and it wouldn’t bother me. In fact I would probably like that. As long as there were no people. I can’t stand people touching me. It drives me mad – instantly. If someone just lays a hand on my shoulder – wham – instant reaction.”

Away from the circuit and pressure Hulme lives up to the “Bear” image. But the friendly “Rupert” type.

“I put on the tough exterior look to keep people away and so they get the feeling that I have got a hate on and don’t come near me. My friends know that this is just like the shell around the walnut, a protection that I put up. A big draw-back is that I am very, very shy. I don’t know why. I’m frightened to answer the telephone or make appointments to see people.”

He also hates writing letters and feels that it is much more efficient to get on the telephone and come to decisions quickly. He also hates the expense account lunch which drags him away from his home to discuss something which could easily have been settled on the telephone.

“All this ‘come up to London and have lunch with me while I sort out a deal’, wastes my time. I’ve got so much time it doesn’t matter but it wastes my time. What’s wrong with a two-penny telephone call to tell me the same thing? It saves the guy buying me lunch so it must be more economical in the long run.”

The fact that he has been a public figure for over 10 years hasn’t broken through his shyness although he feels he can cope a little better than he could.

Privacy is the most valued commodity but when he does make the effort to be sociable he finds that he is driven into the ground by people who only want to know him because he is a famous racing driver. He hates the lack of identity, of being a man, that being asked to a party as a conversation piece, engenders. “I just want to be me.” But being Denny Hulme, ex-Grand Prix World Champion and CanAm Champion makes him more than just an ordinary “me”. He gets opportunities and meets people who the “ordinary me” he wants to be, would never get.

INLINE-MEDIA BIG

Jackie Stewart’s jet-set life amongst the stars of the international society didn’t appeal to Denny. “If Jackie wants to say he knows Roman Polanski, Princess Grace and all those people I couldn’t care less. If Princess Grace wants to get into a bikini and come down onto the beach and sunbathe with me that’s fine. But as for me going up to her castle – forget it.”

For a man earning a comfortable living he is surprisingly suspicious of other people’s hospitality and finds himself drawn to the company of his mechanics in the evenings when he is away from home. He feels that they know him well enough and understand how he feels sufficiently to let him relax. He like a share and share alike basis. He doesn’t like other people paying his bills. “Rich guys who want to pay for everything all the time just to show how big they are really bug me.” He expects everyone he respects to pay their way.

“I would prefer to go to a restaurant, or share a plane or a car and pay my share.

“Everybody paying their way. I don’t want somebody to think they are somebody doling out for everything. That really cheeses me off. I enjoy going out with the mechanics. When we can manage it the entire team goes out to enjoy itself. It’s always been a thing with McLaren that the entire team stay at the same class of hotel. None of this thing that drivers stay at the poshest hotel in the world while the mechanics scrub along in some pokey dump.”

The mechanics seem to appreciate this and it’s rare for McLaren mechanics to be heard complaining about their treatment.

Away from the circuit Hulme keeps in touch and visits the factory two or three times a week.

“I use the shop as a playroom for myself, they have lathes and mills there and I can make a lot of bits and pieces for the house. When I was building the house, if I hadn’t has McLaren’s it would have cost me a lot more than it did. I wouldn’t have paid the price I was asked for some of the things I wanted to be made but I was able to have them because I could make them at the factory.

“I mess around a lot over there and when the mechanics see me come in with bits of the car or bits of the tractor they’ve all got suggestions about how the job should be done and help if they can.”

Now that he is president of the Grand Prix Drivers Association he feels that he has the opportunity to get motor racing on a more business-like footing. His unpopularity doesn’t bother him because he feels that he has never been popular. He admits that he may be mistaken in the way he is going about it but doesn’t think that it has made any difference to him.

“I feel that Grand Prix racing has gone past the stage of being a club thing. I want to see it get on to a better level. A level like golf. Wimbledon? Well that’s a bit of a shambles but, yes, in that class. It has got class in Europe because you’ve got princes and kings and things patronising it, which is good. But the time has come to tidy it up.

“In football the trouble is with people who run on to the pitch. The pitch in racing is the pits and this has got to be tidied up. The heaving mobs have got to be kept out before someone gets hurt. When you go to America, to any stock car race, there is not even a mechanic in the pit lane. Not until the car stops. USAC (United States Auto Club) is exactly the same – no one allowed over the wall unless his car is actually in the pits. This is what I would like to see very much in Grand Prix racing.”

Denny admits that before the problem can be really solved it means a re-think of the whole idea of motor racing. Pit areas must be redesigned. This is going to take some time so in the interim the only measure available is to cut down the number of pit passes issued.

INLINE-MEDIA BIG

“There are about four tickets that are issued by the organisers. Drivers, mechanics, trade – they all need to be in the pits. One other ticket was available – a Press ticket. There weren’t any tickets which said ‘comptometer operator having a holiday’ on them, just ‘Press’ or ‘photographer’. To make sure that the cars function you need the mechanics, the trade and of course the driver. The only ticket which is out of place is the press. So we said to the organisers ‘please curb the ticket situation’.

“But they ignored our request until we were forced to say, ‘Right, no Press passes. Unfortunately this hurt the genuine people.”

At the Austrian Grand Prix matters between the Press, Drivers and Constructors came to a head when a ban was imposed and the journalists and photographers held a protest demonstration at the exit to the pit lane as practice was about to start.

The constructors agreed to make the Press after practice and after much argument and some surprisingly stupid statements from constructors who should have known better a makeshift agreement of sorts was undertaken. The constructors were to print and distribute their own tickets for access to the pits. A proportion of these they would give to the press to be controlled by Bernard Cahier.

“I know this isn’t the answer but we have got to get the social scene away from the pit area. The blokes who get a pass and then discuss the wheelspin their Lamborghini gets going through the Mont Blanc tunnel. It’s this ‘in’ social scene we want to stop. It’s the serious business of motor racing that goes on there – nothing else.”

But the Press are not the only problem Hulme wants the pit lane clear. And this means clear.

“I reckon there should be nobody, gendarmes, carabinieri or firemen, in the pit lane.”

At the start of the year the organisers banded together and call themselves the Grand Prix International. Their aim was to show a united front to the F1 Constructors Association who were demanding more money. The organisers pleaded that they had on money and that unless the constructors accepted what was offered there would be no Grands Prix this year. Then they capitulated and found the money.

“The money the constructors asked for was there. And this year the racing has been fantastic. The circuits have been making a living for a long, long time – and a very healthy living at that. The constructors found out how much money they were making and objected to being screwed. Well maybe a wee bit. I reckon they deserve more money.”

A whole new era is over the horizon. Mechanics should get more money, marshals should be paid, constructors should get more money and the organisers should spend more on circuit facilities. Where’s all the money coming from?

“The money’s there. The troubles that we’ve got at the moment will blow over and by next year you will wonder what it was all about. Motor racing is here to stay. Since it started people have been saying it was finished. The money’s there and the enthusiasm is there. All we have to do is get it right. Sort out the problems and upgrade it to the international sport that it is. You know, one of the big newspapers did a survey on sponsorship in sport and found that more money went into motor racing than any other sport. With backing like that and the right approach we have just got to succeed.”