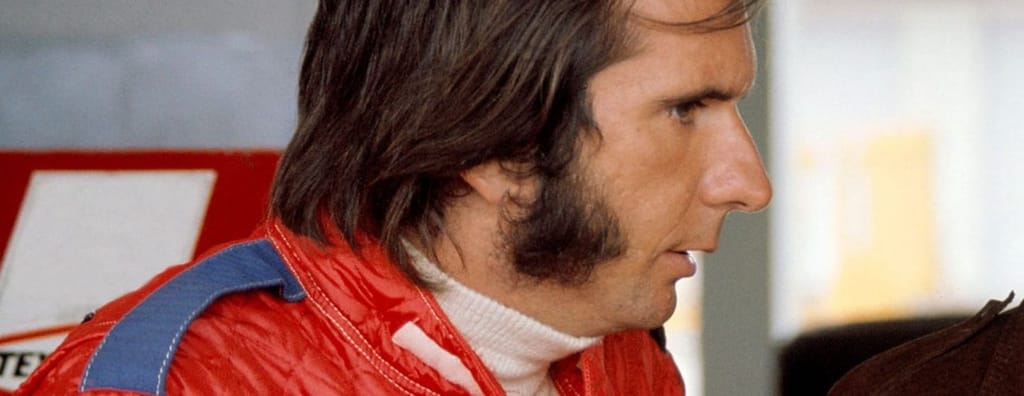

Emerson Fittipaldi

- Born 12 December, 1946

- Titles 2

- Grands Prix 149

- Wins 14

- McLaren Career Span 1974 - 1975

Emerson Fittipaldi led the flood-tide on world-class Brazilian drivers who cascaded into F1™ during the early 1970s and became the youngest ever world champion up to that moment at the age of 25 at the wheel of the sensational Lotus 72. Fittipaldi, by any standards, had a gentle and smooth touch, balancing great natural ability with a sense of tactical perception beyond his years.

Born in Brazil’s bustling second city, Emerson and his elder brother Wilson Jnr grew up in a motor racing mad family. Their father, Wilson Snr, was a respected and experienced motor racing commentator who had first come to Europe with the Fangio/Gonzalez bandwagon during the early 1950s. Emerson followed in their footsteps in 1969, investing every penny he had to purchase a Merlyn Formula Ford car with which to compete in the UK.

His progress through the British junior single seater categories proved to be a revelation, winding up with Lotus boss Colin Chapman bringing him in under his wing. Moreover, after Piers Courage was killed in a grisly accident during the 1970 Dutch GP at Zandvoort, Frank Williams tried to get Emerson’s signature on a contract with his team. But the moment had passed; Chapman had seen to that!

Emerson scored his first world championship points in the 1970 German GP at Hockenheim at the wheel of a Lotus 49C. But then the Lotus game plan dramatically changed forever after Emerson’s team-mate Jochen Rindt was killed in a type 72 preparing for the Italian GP at Monza. Emerson was now a victim of circumstance. Before the season came to an end, he’d won the US GP – only his fourth world championship round – at Watkins Glen in upstate New York – and seemed set fair for a seamless advance towards the championship the following year. In fact, during 1971 Emerson lost some of his career’s momentum. He was quite badly knocked about in a road accident and his US GP victory had unrealistically raised his expectations. He finished a strong sixth in the ’71 championship with a second in Austria and a third at Silverstone; those results kick-started Emerson onto the right track once more and he got the job done in fine style in 1972.

Chapman, of course, was never happy with the status quo and was always seeking some way to exert an edge over his rivals. Just to keep Emerson on his best form, he signed the prodigiously talented Ronnie Peterson to keep him sharp. The Lotus boss realised that such a strategy risked unsettling and irritating his star driver, but with Ronnie now on the payroll this was a move he was prepared to risk. Emerson got on personally very well with Ronnie, but quickly realised the danger of having two top-line drivers in the Lotus squad; they split the wins and let Jackie Stewart through to win the title for the Tyrrell team.

Emerson was not amused and by the end of the season had accepted a lucrative offer to join McLaren in 1974, quickly demonstrating the wisdom of that move by taking the ’74 championship in the Marlboro-liveried machine. For 1975 the Cosworth-engined McLaren M23 was marginally outgunned by the more powerful Ferrari 312T, but Fittipaldi took a strong second to Lauda in thr championship race. He then dropped a bombshell by announcing that he was quitting McLaren for 1976 to join his brother Wilson’s fledgeling F1™ team which was backed by Copersucar, Brazil’s state-run sugar marketing cartel.

In retrospect, this was a case of ill-judged patriotism and family loyalty and was seriously out of focus. It effectively destroyed Emerson’s F1™ career long before his talent had waned. There were only a few moments of sparkling talent to be displayed, notably when Emerson stormed home to second behind Reutemann’s Ferrari in the 1978 Brazilian GP at Rio, the last time he would be cheered to the echo by his home crowd.

From then on, it was downhill all the way and although Emerson stopped driving at the end of 1980, to concentrate on team management duties the following year, lack of sponsorship caused the Fittipaldi team to sink terminally into F1™’s financial quicksands and they finally closed their doors for good at the end of 1982.

1974 in Pictures: #HisNameIsEmmo

1974 in Pictures: #HisNameIsEmmo

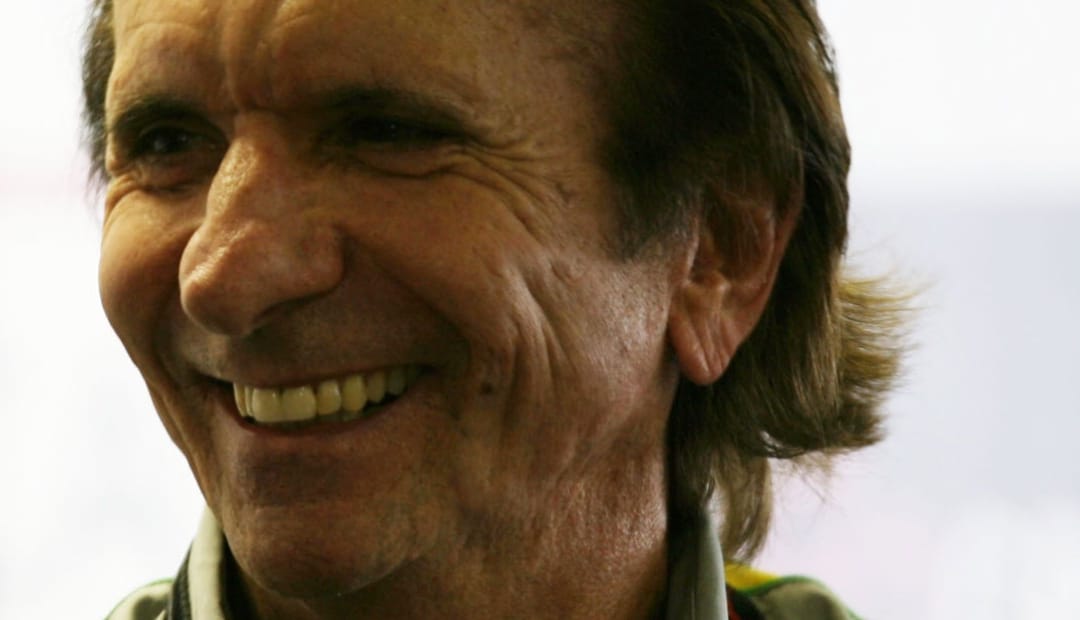

Emmo talks Indy

What did the two-time Indy 500 winner think of McLaren's return?

Fittipaldi returns to McLAREN!

McLaren Formula 1 announce that 1974 Formula 1 World Champion Emerson Fittipaldi will write a monthly column for the team's website.

His name is Emerson Fittipaldi

Celebrating 40 years since Emerson Fittipaldi drove home McLaren's first World Championship title, in 1974. Watch our special 40 years commemorative video and find out more.