Courting controversy | James’ 1976 championship pt. III

In July we took the story of James Hunt’s 1976 World Championship year up to the mid-season British GP. In the third part of our series we recall how the second half of the season set up that memorable finale at Fuji between Hunt and Ferrari’s Niki Lauda.

James Hunt left the British GP on a high. Not only had he won his home race in some style, but he’d also recently been reinstated as winner of the Spanish GP, after an appeal against his original exclusion. He now had 35 points, and was thus still some way behind the 58 of Niki Lauda, but with seven races still to run, and the momentum seemingly going in his favour, it was far from over. However, no one could have predicted how the upcoming German GP would turn the World Championship battle on its head.

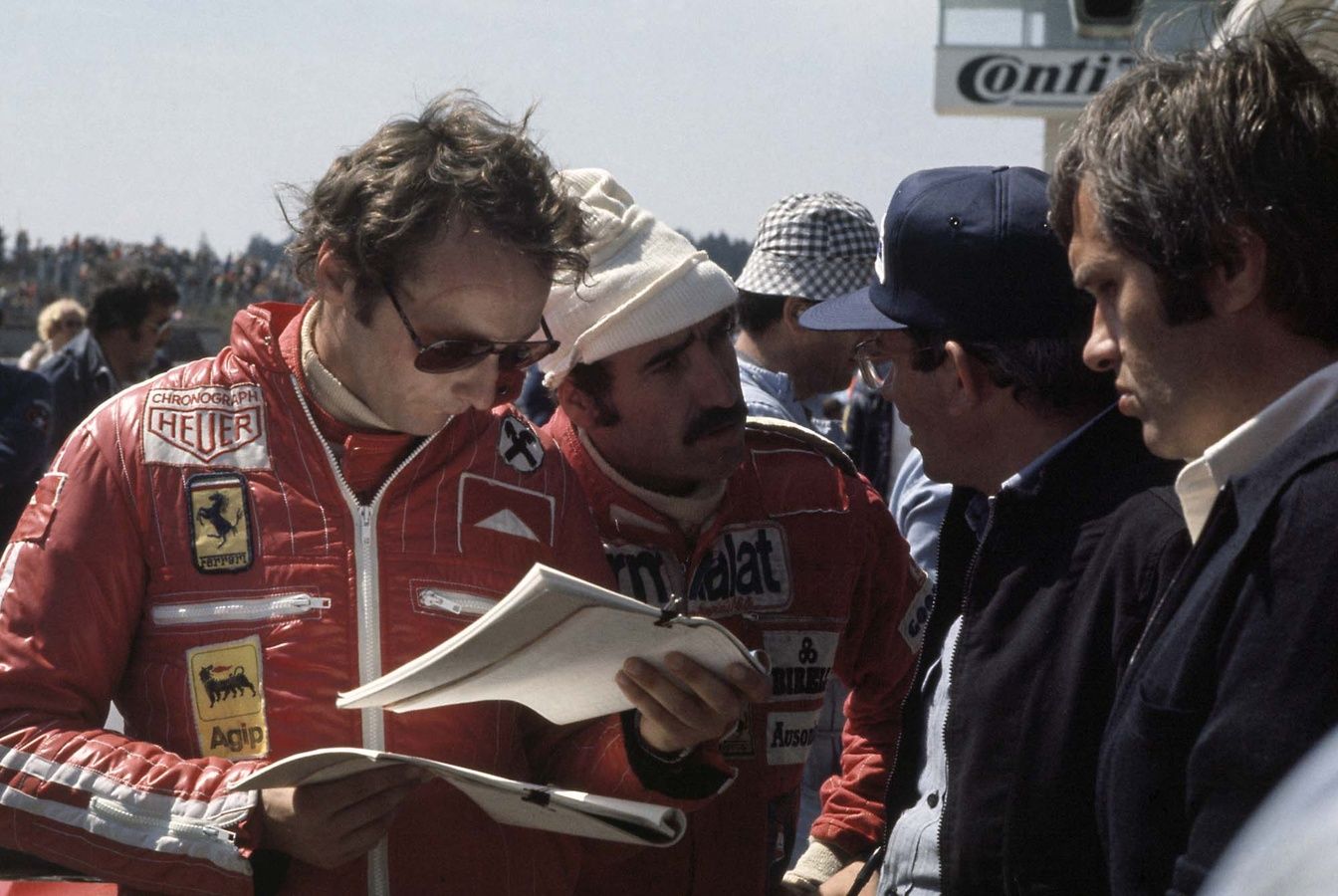

The build-up to the Nurburgring race was dominated by concerns over safety. Many drivers believed that the sport had outgrown the daunting venue, and doubted the ability of officials to properly marshal its full 14.1-mile length. No one was more vocal than Lauda, who made his feelings known in the media.

Typically, once in the cockpit the Austrian was able to put his concerns behind him. By the end of Friday’s practice he was second fastest, beaten only by Hunt – also not a big fan of the track. When Saturday proved to be a washout, with discussions over safety in wet conditions dominating the day, the grid was set.

The rain continued into Sunday, although it had abated by the race start. Nevertheless wet-weather tyres were the obvious choice. One man who thought differently was Hunt’s McLaren team mate Jochen Mass, who checked with a local official who had just driven round, and was told that the farthest reaches of track were indeed drying. At the last minute he switched to slicks, while James concluded that it would be wiser to follow what the majority of his rivals were doing.

It was a brave and inspired decision by Mass, and a correct one.

It soon became apparent that the track was becoming too dry for wets, and after the start the German driver gradually worked his way up the order. At the end of the first lap only Ronnie Peterson, still on wets in the works March, flashed past the pits in front of Jochen. Behind them Hunt decided to pit from third place and take on slicks, and he was followed in by Lauda – who had dropped to eighth on a scrappy first lap – and much of the rest of the field.

By the end of the second lap Mass was in the lead, and Peterson and others who had not yet stopped pitted, allowing Hunt up to second. However, several cars were missing from the lap chart and when officials stopped the race, it was evident that something significant had happened.

It soon emerged that Lauda had crashed heavily before the right-handed Bergwerk corner. His car had slewed off the road as it tackled a minor left kink, then rebounded onto the track, where it was struck by the cars of Harald Ertl, Brett Lunger and Guy Edwards, and it had burst into flames. Lunger, Edwards, Ertl and Arturio Merzario had all piled into the fire and pulled the Austrian clear. His helmet had been dislodged, and he had burns to his face.

Mass, Hunt and the others running ahead of the accident parked before they reached the scene on their third lap. On returning to the pits James was led to believe that Laudas injuries were not too serious, and he was still under that impression when he went to the grid for the restart, on what was by now a fully dry track.

Hunt had made some poor starts over the season, but, as at Brands Hatch – another restarted race – he did a much better job second time around. At the end of the first lap he already had a handy lead, and he went on to win comfortably ahead of Jody Scheckter and Mass, who was hugely frustrated and disappointed to have lost the chance to win his home race.

James now had 44 points to the 58 of Lauda, but that soon became academic when the full extent of Niki’s injuries became clear late on Sunday evening and into the next day. His burns were more serious than had been thought, but the big problem was the damage done to his lungs. For the next few days his life hung in the balance.

“We were very concerned but there was little or nothing we could do,” Hunt said in his book Against All Odds. “I couldn’t visit him, so I went home and sent him a telegram. I can’t remember what it said, but it was something provocative to annoy him and then it told him to fight, because I knew if he was annoyed and fighting, he would pull through. If he relaxed and gave in, he would probably die.”

As the world awaited more news about Lauda his Ferrari team, citing frustration over the Spanish and British GP controversies, withdrew from the following race in Austria.

When Hunt qualified on pole at the Osterreichring it looked likely that he would earn another nine points, but he made a bad start and eventually finished fourth, having been slowed by front wing damage.

Instead, a first victory went to Penske’s John Watson, who had been showing increasingly good form. James had taken just three points out of the absent Lauda’s lead, but with the scores now standing at 58 to 47, it was close. At that stage few imagined that Niki would race again in 1976.

By the time of the Dutch GP the news on Lauda’s status was more positive, and there was now serious talk of him returning to the cockpit before the end of the season. This time Hunt was beaten to pole by Peterson, and in the race he had to pass the Swede and fend off a determined Watson before he finally claimed victory, despite a loose front brake scoop hampering the aerodynamics. It was his 29th birthday, and also the first anniversary of his maiden win with Hesketh. And he was now just two points shy of Lauda’s total of 58 with four races to run.

Well aware that his precious advantage was slipping away Lauda performed miracles to get himself fit enough to return to action at the Italian GP, after a test at Ferrari’s Maranello test track, Fiorano. His head was still swathed in bandages, and the lining of his helmet was modified to lessen the pain. It was by any standards a heroic effort.

This already controversial season took another twist when after Saturday practice Italian officials tested fuel samples, and deemed that those from McLaren and Penske exceeded the permissible octane limit. There were question marks about their conclusions and methodology, but the bottom line was that Hunt, Mass and Watson lost their Saturday times and had to rely on those from Friday – when it was raining heavily. Initially they were deemed to be non-qualifiers, but all three would eventually start at the back of the grid.

It was to be one of the worst days of Hunt’s season, as he fought his way into the middle of the field before sliding off at a chicane while battling with Tom Pryce, much to the delight of the partisan crowd. Lauda in contrast recovered from a bad start and finished a remarkable fourth, earning three vital points and extending his lead over Hunt by 61 to 56.

There was to be more bad news for James in the following days. Ferrari had launched an appeal after the controversial British GP, and after it was heard the McLaren man was stripped of his win, having deemed not to be running when the race was red-flagged. In an instant he lost nine points, while Lauda gained three, having been promoted to winner. It boosted his advantage to 17.

James was already in Canada preparing for the next race when he learned the bad news via a phone call to a squash club where he’d gone to relax.

“The worst moment for me this season came when I heard that I had been disqualified from the British GP,” he told the Daily Express. “It was so obviously and totally impossible for us to be disqualified that I had half expected it to happen. I have learned in life to expect that sort of thing.

“Combining this with the Italian fiasco I felt really cheated – yes, cheated. Here I was in a position to win the World Championship after 10 years of effort and here I was being politically assassinated, being cheated by events over which I had no control whatsoever.”

He knew now that he had to win the next two races to give himself a chance of taking the battle to the final round in Japan. At Mosport in Canada he earned another pole, but in the race he had to pass Peterson to guarantee victory. Lauda meanwhile had a frustrating race due to a rear suspension issue, and failed to score. The gap was back down to eight points.

At the penultimate race, at Watkins Glen in the USA, Hunt took yet another pole, but once again he didn’t have it easy in the race as Jody Scheckter led early on for Tyrrell. James said later that he felt he was driving “like an old grandmother,” but he forced himself to focus, and eventually caught up and found a way past the Tyrrell. As he explained, “This was the most important race of my life. I simply had to win.” Meanwhile Lauda came home third after just holding off Mass, earning himself four priceless points.

The result ensured that Niki led James by 68 points to 65 as everyone prepared for the final race of the season, the first World Championship event to be held at Fuji Speedway in far away Japan, a circuit that nobody had raced at before.

As Lauda headed home to Europe for further medical attention Hunt flew to Tokyo, in order to acclimatise to the time zone and – crucially – get in some precious testing at Fuji.

McLaren was leaving nothing to chance as the title decider approached.

Click here to read Part One: On the Hunt | James’ 1976 championship